Spectech Lessons and Updated Hypotheses from 2025

Things we got right, things we got wrong, and things we didn't know we didn't know going into 2026

In the spirit of being an institutional experiment, we are continuing the tradition of sharing our takeaways from 2025: what we want to double down on, got wrong or updated our beliefs on from last year’s hypotheses and new hypotheses going into 2026.

Double Down:

Governments run into fundamental tensions around ambitious research.

Materials and manufacturing are an incredibly impactful place to focus for new institutional models.

Exclusively working with external performers in the 21st century is severely limiting.

Universities need to be unbundled.

As an organization, we need to figure out how to use AI well.

Updated/Wrong

Coordinated research programs are now bottom-of-the-funnel limited.

New

A lot of technology work makes sense neither for venture funding nor philanthropy.

There’s a specific new manufacturing paradigm we should focus on.

We need to build a physical home for misfits and ambitious researchers.

It is so much easier to make progress on ambitious research when you are already doing things.

There’s a reason people rarely want to fund the high-risk part of high-risk high-reward research — successful projects need to right-side upside adjusted risk.

Deadlines are incredibly powerful.

2025 was a weird year in the research world

There was a lot of volatility where the research world touched the government: suspended or revoked grants to universities, hiring freezes and personnel turnover at the ARPAs and other research agencies, and immigration status uncertainty for the many non-citizen scientists in America.

Many new initiatives happened as well. In the US, the Genesis Mission was announced, NSF released an RFI about a new “Tech Labs” initiative, and OSTP explicitly called for new ideas in how science is funding. Internationally, ARIA launched a “FRO founder residency” and Japan launched their Global Startup Campus.

In the private sector, “AI for science” had a big moment. While what “AI for science” means is still evolving, right now it is particular focused on drug and materials discovery. Periodic Labs, Lila Sciences, and Jeff Bezos’ Project Prometheus raised huge amounts of money among others. Basically every big AI lab announced that they had some sort of science initiative.

Double Down

Governments run into fundamental tensions around ambitious research. This year illustrated why one of our big theses is that we (and other ambitious research orgs) need to depend primarily on private funding. People regularly ask the (reasonable!) question “isn’t this the sort of work the government should fund? Can’t the government deploy far more money towards pre-commercial research than the private sector?” But two things are true simultaneously:

The officials in democratic governments need to justify spending to voters

A lot of the work that goes into ambitious research is hard to justify until long after the fact, if ever. (And most officials and voters do not viscerally understand this through no fault of their own.) We saw this dynamic play out on the national stage this year. I’m not going into the politics of the whole thing but there was a lot of research funding that a chunk of officials and voters did not think was justified and it was cut off midstream.

Materials and manufacturing are an incredibly impactful place to focus for new institutional models. The past year, materials and manufacturing were really in the spotlight both because of geopolitics and AI. The “impactful” piece is much more consensus than it was a year ago. But most of the work is being done in the form factor of old institutional models: startups, accelerators, and academic labs. Particularly, the timescales and system-level work that needs to happen raise questions whether this work will deliver on its promise. Time will tell.

Exclusively working with external performers in the 21st century is severely limiting. I’ll point at updates from 2023 and 2024 for most of the reasoning but as additional evidence, the Impossible Fibers program actually built a lab (thanks to the Astera Residency!) and both immediately started learning far more and executing far faster than when it was working to coordinate academics and startups.

Universities need to be unbundled. We first hypothesized this before all the trouble the universities ran into in 2025. Doubling down is not meant to kick universities while they’re in trouble, but the events of the past year illustrate the case for unbundling. The government used cuts to scientific grants as leverage to get concessions around issues that largely had nothing to do with technical research. The financials of many institutions are under threat because of fewer international grad students. Putting so many societal functions in one basket makes them all mutually vulnerable.

As an organization, we need to figure out how to use AI well. This is perhaps more true going into 2026 than it was going into 2025. “AI for science” was abuzz in both the private and public spheres. It’s a far bigger topic than any one organization (and frankly a lot of it is still navel-gazing) so, while we did dip our toes into the bigger discussion, in 2026 we’re going to focus on our sphere of influence and competence. Specifically, we’re asking two questions:

How can we use AI at Speculative Technologies to improve the work we do both creating technology and helping people start programs to do so?

How can people creating and running ambitious research programs leverage AI more effectively?

We suspect that models with the right context could give feedback that, while it isn’t a substitute for an experienced mentor, can give good solid feedback in a tight feedback loop. We’re starting to take advantage of coding tools to build systems and tools for gathering information and sharing it with the people we work with. I’m hoping to make building custom tools to become a knee-jerk instinct for everybody in the org, regardless of experience. In addition to helping people starting and running programs in obvious ways like finding the right people to talk to, there are surely many useful ways to leverage AI for doing technical analyses and detailed technology roadmaps.

Updated

Coordinated research programs are now bottom-of-the-funnel limited. That is, the bottleneck to more ambitious programs (especially those run by people who don’t look like traditional research leaders) is the number of people and organizations who want to support/fund them. This wasn’t necessarily the case a few years ago when the concept of an FRO was brand-new and running an ARPA-like program wasn’t on the radar of most people outside of researchers who had previously interacted with DARPA or its kindred organizations. Now that “ARPAs” and “FROs” are much more in the public consciousness, many more great people want to start programs than there are homes or support for them.

New

A lot of technology work makes sense neither for venture capital /nor/ philanthropy.

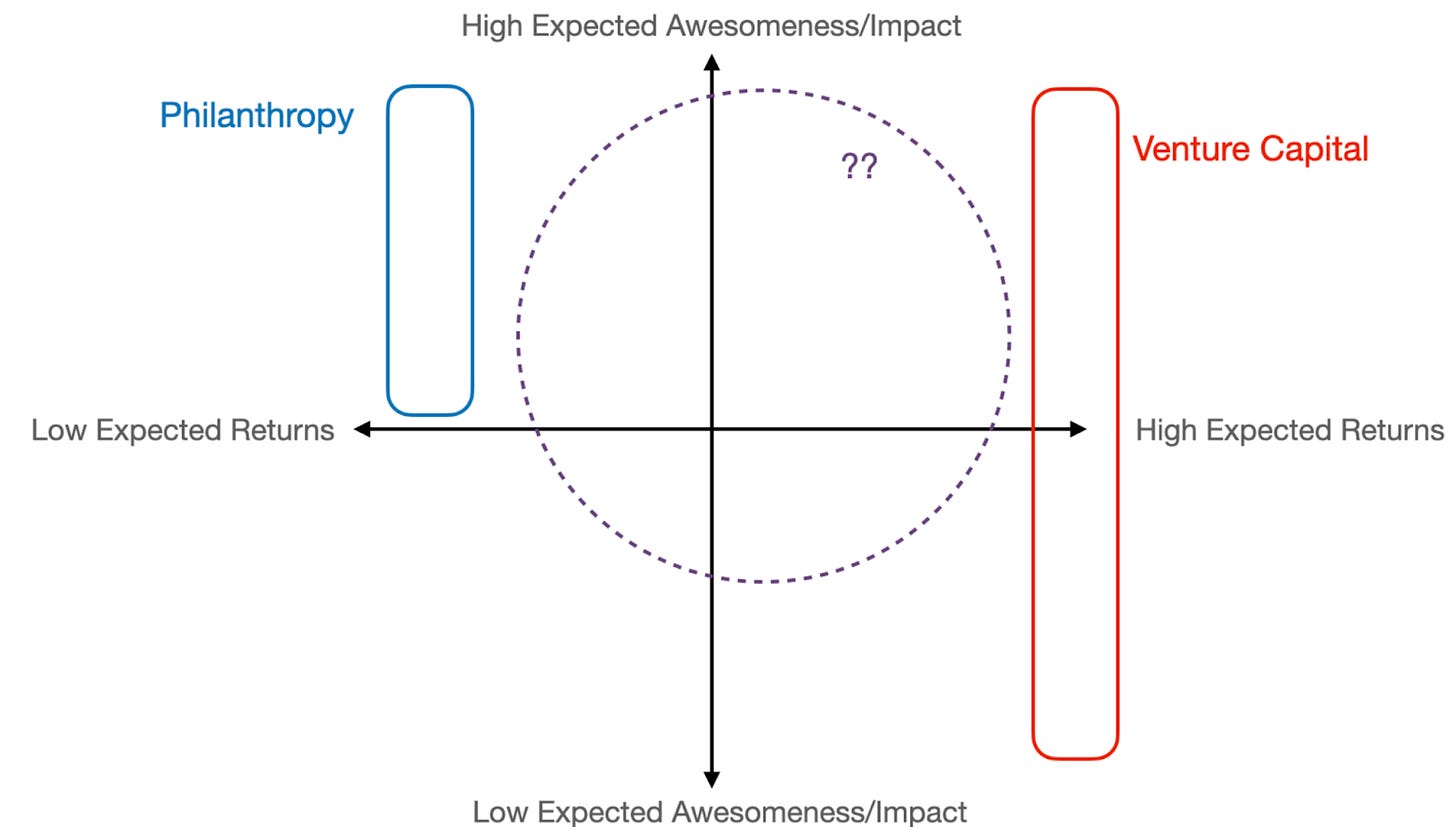

Today, most private capital for ambitious science and technology efforts falls into one of two categories: philanthropic funding, which supports work with no expectation of financial return, and venture capital, which demands high returns on relatively short timelines. However, a big chunk of transformative science and technology is a poor fit for both buckets. These efforts may ultimately generate commercial value, but the path to doing that doesn’t look like a team building a clear product for a long time; often it’s not even the original team that creates the commercial value. This puts that work in a gray area: it’s both too “commercial” for traditional philanthropy, and not commercial enough for venture capital. This misalignment creates a structural funding gap—one that leaves potentially world-changing ideas without the catalytic support they need to move from lab to real-world impact. The challenge is compounded by high uncertainty in both expected impact and financial return, making it even harder for traditional capital sources to engage.

You can see this gap if you map technoscientific work onto two axes — one for expected returns and one for expected awesomeness/impact. This gap is compounded by the fact that a lot of work has high uncertainty around even its expected returns and impact.

So, the question is — how can we change the world to support science and technology work in this “missing middle?” We’ve realized we need to focus more on that question.

There’s a new manufacturing paradigm to be created around tooling-free, rapidly reconfigurable cells. From day one, we’ve identified materials and manufacturing as one of the most impactful places to do technology research. Going into 2026, we’re especially interested in the pieces of a potential new paradigm that leverages new tools and physics. You can see the sketches of what that paradigm might look like here.

We need to build a physical home for misfits and ambitious researchers. This hypothesis is perhaps the logical extension of working with external performers being limited and where work happens being important. In the spirit of intellectual honesty, this is exactly what I called out in 2020. What I didn’t understand at the time is why there’s a strong attractor towards internalizing work, especially with modest resources in the 21st century.

“The dominant paradigm of starting an org is to do internalized R&D unless you’re a government or charitable foundation. In reality, R&D orgs lie on a spectrum between externalized and internalized, with DARPA on one end and Lockheed Skunkworks on the other. Externalized research entails working through grants and contracts while internalized research is doing everything in house. There’s nothing inherently wrong with building a Skunkworks – it just means that there are different tradeoffs and the statement “DARPA for X” is misleading.”

It is so much easier to make progress on ambitious research when you are already doing things. A pattern we’ve seen over and over now is that once people doing ambitious researchy things, there’s an inflection point where opportunities just start opening up. This makes sense: it demonstrates that you and a team can execute and showing real outputs makes an idea concrete in a way that storytelling never can. Somehow people are far better at imagining the possibilities for a technology and organizational capabilities when they can see even pieces of it in reality. You can’t start arbitrarily small: you need enough resources to get over some amount of “activation energy” and resolve some amount of uncertainty that varies on an idea-by-idea basis. But that amount is often less than people think. It’s tempting to let the perfect stand in the way of the good — “I need $50M or bust. The problem is so complicated that there are no intermediate milestones.” This year we’re going to lean hard on the question of “what is actually the smallest unit of real work you can do to make the thing real?”

There’s a reason people rarely want to fund the high-risk part of high-risk high-reward research — successful projects need to right-side upside adjusted risk.

We see several patterns over and over:

A nonprofit or government organization announces an ambitious, very expensive research project or organization to do “high risk, high reward work”. Heavily credentialed leadership is brought in, committees of experts are given meticulous oversight, and/or every decision needs to be run by the principal. Things move slowly, maximally conservative decisions are made, and approaches are slowly nudged towards established “best practices”. “Good” work happens, but nothing great or notable.

Coordinated research programs that want to do something that is risky and new but requires a huge chunk of capital go unfunded, while startups that are doing things that are even newer and riskier raise far more money.

Successful efforts to do ambitious things in a new way find ways to start doing work with a relatively small amount of resources.

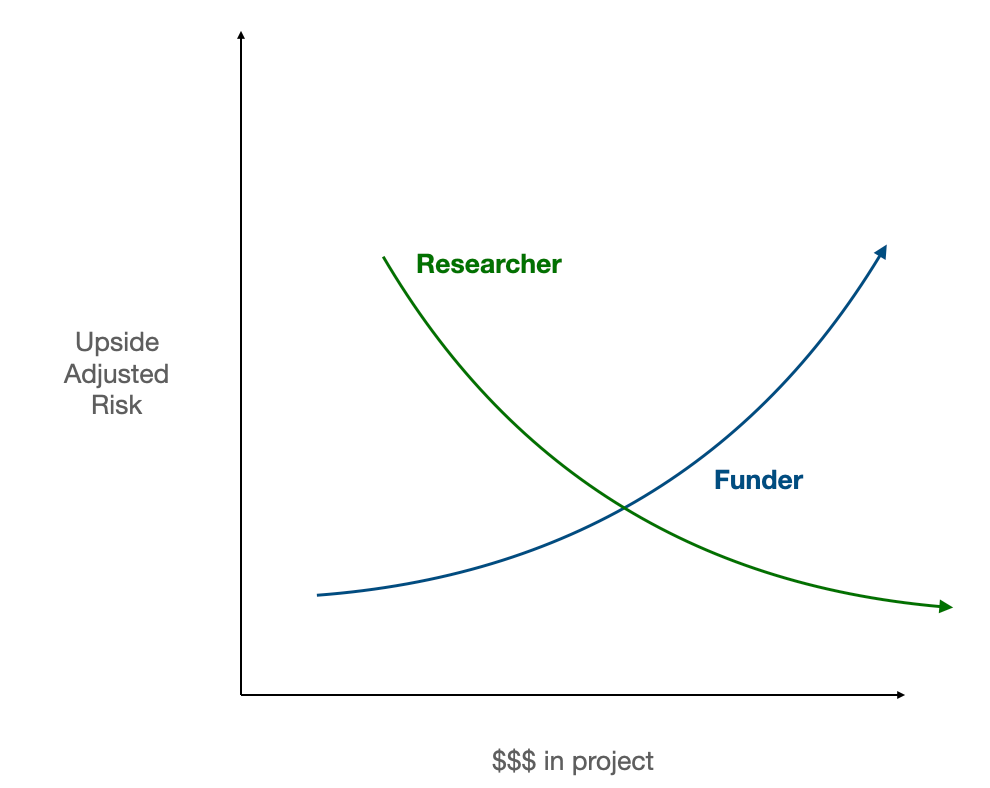

The synthesis here is an idea that I’ve termed the distinctly uncatchy “right-sizing upside-adjusted risk.” Basically, the more money that gets deployed in one go, the more people need to see one of two things: lower risk, or more upside to them personally. The reality is that most work without a financial upside does not have huge potential upside for the people involved in funding them. The program manager who made the DARPA grand challenge happen (Ron Kurjanowicz) is not a household name nor incredibly wealthy (I assume based on base rates and no information otherwise — I don’t know his personal finances nor is it any of my business). Funding the plant breeding research that has arguably saved millions of lives or supporting molecular biology as a field are merely footnotes in John Rockefeller’s biography, and most of the impact happened after he died.

Researchers also evaluate work based on upside-adjusted risk, though their curve is almost the inverse of a funders’. Quitting your job to work on a startup that has only raised $1M is a different proposition than quitting your job to work on an FRO that has raised $1M for two reasons: there’s both a possibility that you can become a millionaire if the startup is successful and the ecosystem for follow-on FRO funding is less developed. That is, the upside is lower and the risk is higher.

If we chart the upside-adjusted risk for both funders and researchers, they have roughly the opposite shapes. Right-sizing is the nontrivial task of crafting a point where they intersect.

This year we’re going to both try to help people figure out this right-sizing problem and try to nudge the world towards systems that make starting small more feasible, like committed tranches.

Deadlines are incredibly powerful. There’s a cultural sense that research should be free of constraints; that ideas will come when they come. Perhaps stemming from and embodied by Vannevar Bush’s quote that “Scientific progress on a broad front results from the free play of free intellects, working on subjects of their own choice, in the manner dictated by their curiosity for exploration of the unknown.” But the reality we’ve found is that external deadlines help even focused, ambitious researchers. The old adage that “work is like a gas — it expands to fill the time given to it” is doubly true in high-uncertainty situations with infinitely deep rabbit holes to go down. Many Brains fellows have told us that the most useful part of the program were the deadlines. While I think that’s true, deadlines are the tip of an iceberg: you need to take them seriously, which means that you need to believe that the goal the deadline is for is useful and trust the entity imposing the deadline. Setting up those conditions is hard. In 2026 Spectech is going to lean hard into the power of the deadline, both internally and externally.

Here’s to a 2026 full of ambition, outputs, and learning!

Who does something similar to you in europe?