Spectech Lessons and Updated Hypotheses from 2024

Things we got right, things we got wrong, and things we didn't know we didn't know

In the spirit of being an institutional experiment, we wanted to share some of the key takeaways from 2024: what we got right and what we are updating from our hypotheses going into the year, some lessons from 2024, and then outline some big hypotheses going into 2025.

In addition to our actual outputs, we hope that through the feedback loop between meta-scientific ideas and executing on those ideas, we can pave the way for other institutional experiments. I realize that each of these points wants its own memo unpacking it. I hope to create those over the coming year.

Below is a summary of our takeaways, divided into hypotheses from last year that we want to double down on, beliefs that we have updated or were wrong about, and new hypotheses going into 2025. I expand on each one further down. (As a gentle nudge that we are subscriber- and donor- supported, the updated and new hypotheses are paywalled for now.)

Double Down:

There are far more ideas that don’t fit into existing institutions than a single organization can handle.

Governments run into fundamental tensions around ambitious research.

Working with Bureaucracies is incredibly hard for a new organization.

Materials and manufacturing are an incredibly impactful place to focus for new institutional models.

Universities have developed a monopoly on pre- and non-commercial research.

Exclusively working with external performers in the 21st century is severely limiting.

Updated/Wrong

Corporate research has been gutted.

It is harder to fund 1-off ambitious research programs in materials and manufacturing than we thought.

There are a lot of subtle annoying things about nonprofits.

New

Universities need to be unbundled.

PI-based funding is holding back progress.

As an organization, we need to figure out how to use AI well.

There are a lot of systemic things widening the ‘valley of death.’

In many domains, IP is net negative.

Double down

I think most of our hypotheses going into 2024 were spot on. I’m not going to touch on all of them, but I’ll highlight the most important ones that I want to double down on and the additional evidence for them.

There are far more ideas that don’t fit into existing institutions than a single organization can handle. Throughout 2024, we constantly ran into people with ambitious ideas that don’t fit into normal institutional boxes: some of them were stuck, some of them were struggling to cram their ideas into normal-shaped boxes, and a small-but-increasing number are forging their own path. We acted on this one by running the Brains Accelerator, publishing the Research Leader’s Playbook, and starting a growing network of people running out-of-the-ordinary research organizations.

Governments run into fundamental tensions around ambitious research. We spent quite a bit of time exploring possibilities for government funding and were mostly disappointed: everything from the important work being too use-focused for basic research grants and not specific-application-focused enough for applied contracts, to falling outside rigid categories, to grants that can only go to accredited universities or startups. Furthermore, working with the government eats time that a small team can barely afford: it takes many hours to even sign up to be eligible to receive contracts and we literally had the discussion of “this contract isn’t big enough for us to go for because it doesn’t cover the additional person we would need to hire to handle the reporting.” These government constraints are coupled to another lesson from last year that I want to double down on: Working with Bureaucracies is incredibly hard for a new organization.

Materials and manufacturing are an incredibly impactful place to focus for new institutional models. 2024 convinced me this is more true both on the impact piece and the need for new institutional models. (See here and here for much more on that.) Based on these pieces, I now run into so many people with ambitious ideas in materials and manufacturing who are like “yup, neither academia and startups are any good for making these things happen.”

Universities have developed a monopoly on pre- and non-commercial research. 2024 hit us over the head repeatedly about how difficult it is to avoid interfacing with universities when you’re doing any sort of research that isn’t obviously a business and how much bureaucracy and weird institutional incentives that brings. Experts? University. Lab space? University. A government or foundation wants to set up a new research-adjacent initiative? It will inevitably be anchored to a university. This needs to change. Two anonymized anecdotes on this front:

I talked to [a state government] that is working to create a new [hype-y topic area] hub. The hub is of course run by [a prestigious university]. I asked about when I should expect updates. The state official said “no idea, we’ve been waiting months on the university.”

An acquaintance who had spent years working in several departments of the US federal government went to [a prestigious university] to start a new initiative there. He rage-quit a few months later because it was even more bureaucratic.

Exclusively working with external performers in the 21st century is severely limiting. We did a lot of work trying to coordinate work between different organizations. I need to start tracking how much time is wasted haggling over non-existent IP, trying to align incentives and timescales, all of which is compounded by how so many organizations (even startups!) are basically run by lawyers.

Updated/Wrong

Corporate research has been gutted. In 2024, we spent quite a bit of time exploring whether we could fund programs by building a consortium of corporate sponsors who would all benefit from the technology. What we learned was sobering. Many people we talked to were interested, but not only did they not have money to spend on external research by a weird new organization, they didn’t have money to spend on exploratory projects in their own organization. The prototypical situation (exemplified by a lab I won’t name but used to be mentioned in the same breath as Bell Labs) is now that half of the research org’s funding comes from direct contracts with operating units to do extremely scoped work to improve existing products and the other half needs to come from external contracts. Obviously there are exceptions, but I don’t think we can count on modern corporations to fund ambitious new technologies. (There is much more to be written about the why here and whether it will change.)

It is harder to fund 1-off ambitious research programs in materials and manufacturing than we thought. We thought that it would be possible to incubate FRO-ish programs in our focus areas and raise money for them on a program-by-program basis, similar to how Convergent Research operates. Our results were frankly dismal. There are a number of reasons for this:

Materials and manufacturing doesn’t resonate with philanthropists. The vast majority of research philanthropy goes towards health, climate, and basic science (in that order). If you are working on technology that isn’t directly targeting those areas, philanthropic fundraising is an uphill battle … in the snow.

It’s very hard to get grants or contracts without existing infrastructure/without already doing the thing. This creates a chicken and egg problem.

Most systems expect the principal investigator/program lead to do fundraising, but many otherwise awesome program leads just don’t have great networks and aren’t great sales people. It is even harder to break into research fundraising than it is to break into VC fundraising; while any sort of leadership requires some amount of “sales,” many people who would be great program leads aren’t necessarily great at selling research programs in the way that you need to in the current environment. The Brains accelerator is an attempt to address this, but it can only do so much. (This is tied to the lesson below about PI-based funding.)

There are a lot of subtle annoying things about nonprofits. Last year I doubled down on the hypothesis that being a nonprofit is important. I still think that given US equities-driven profit expectations, the ratio of positive externalities we expect to produce, and our long timescales, being a nonprofit is still our best option. (You can see the extremely rough monte-carlo analysis that leads me to believe that here.) However, 2024 has really hammered home that there are a ton of non-obvious annoying things about nonprofits:

Nonprofits can’t sell parts of themselves or be acquired. This fact creates a lot more fighting over nebulous things like credit and relationships. Counterintuitively, it also creates more zero-sum games because if two organizations are doing the same thing, there is no option for one to buy out the other.

If you have extra cash in the bank, you can’t get normal high-yield checking accounts.

External entities and organizations expect to have a lot more control over how money is spent in a nonprofit, which makes it much harder to make high risk/reward bets that are hard to justify externally.

There’s an expectation that nonprofits should be doing everything at-cost. Just because an organization isn’t out to generate a profit for shareholders doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be able to do high-margin work that subsidizes other parts of the organization.

New

Universities need to be unbundled. This hypothesis is a corollary of the realization that universities have developed a monopoly on pre- and non-commercial research and exclusively working with external performers is limiting. Universities have become a massive bundle of societal roles — from sports team to moral instruction to discovering the secrets of the universe to hedge fund — run by giant bureaucracies that are doing an inevitably poor job balancing them. We need new organizations to specialize in tackling subsets of these roles. Universities are especially poorly suited for working on pre-commercial technology research and speculative technologies, and we should create a home for misfits who want to do that work.

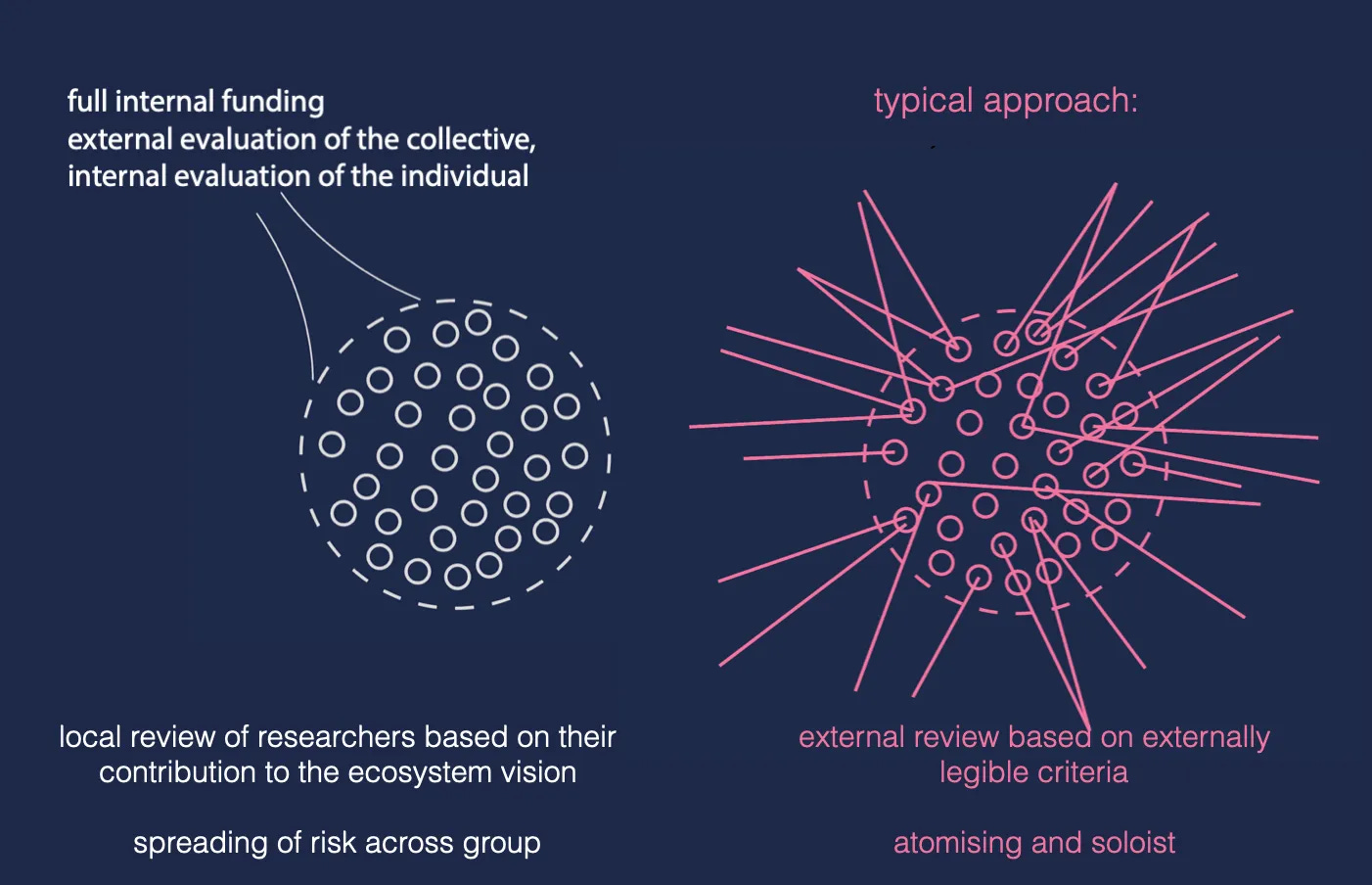

PI-based funding is holding back progress. In 2024, we spent a lot of time with research leaders across many kinds of organizations; the constraints imposed by PI-based research funding came up constantly.

The vast majority of research funding is based around primary investigators (PIs). That is, a grant or contract is awarded to a specific person within an organization to do a specific project. The expectation is that the PI has come up with the idea, is the main technical expert, and is responsible for managing the whole project. The PI is also expected to be the one taking point on applying for the grant or contract. The prototypical PI is a professor at a university with a research group, but PI-based funding doesn’t just dominate university funding – it’s the norm for a lot of corporate R&D, national labs, contract research orgs, and many weird new things as well. And it’s not just the government that expects to fund PIs for specific projects, but philanthropy and corporate research as well.

This isn’t the place to dig into all the negative effects of PI-based funding — everything from the best researchers spending 40% of their time writing proposals to warping the skillsets of research leaders and their career tracks to the “organizational pincushion effect” where external organizations reach in and modify the internal incentives of a research organization on a project-by-project basis.

From: https://jameswphillips.substack.com/p/my-metascience-2022-talk-on-new-scalable

Right now our ability to change this as a small organization is limited. But we can still flag the problem and do everything we can to mitigate the burden on people we’re working with.

As an organization, we need to figure out how to use AI well. While I don’t think AI is going to replace researchers anytime soon, I suspect that AI can be an important tool for a research org. There are the obvious things — generating first drafts of proposals, editing writing, creating sticker designs — but I suspect there are many more powerful non-intuitive things we could use it for. I also suspect it will take quite a bit of work to figure it out, so I’m trying to carve the space for us to take the short-term productivity hit to experiment. Organizations that take best advantage of new technologies figure out how to reconfigure around them instead of just using them as drop-in replacements for steps in existing processes. What is the equivalent organizational reconfiguration to how electric machines let organizations build factories around material flow instead of steam-driven power shafts?

There are a lot of systemic things widening the ‘valley of death’. I’m kind of obsessed about the fact that in the late 19th century people could just start technology businesses by borrowing some money from friends and family, building one or two of a thing, selling those, and then use the revenue to build more of them. Contrast to now when you need to raise a ton of money before selling the first product. We don’t talk enough about how the “valley of death” seems wider now than in the past.

Part of it is likely that creating new technology has become more expensive (although I have not actually seen a systematic study on how the cost of building individual technologies has changed over time). However, I suspect a lot of it also has to do with other factors: the additional time and costs associated with building factories, getting regulatory approval, increased safety and quality expectations from consumers, societal risk aversion, and the decreased risk and increased rate of return from equity markets.

In many domains, IP is net negative. Over the past year, we’ve run into many situations where intellectual property (IP) considerations drastically increase transaction costs — wasting tons of time, creating secrets and miscommunication, and potentially killing collaborations — with very tenuous upside. While there are probably domains where IP is a net positive (probably single-molecule drugs, for example) I’m starting to believe that there are enough hidden externalities from patents in most domains that they are a net negative for the world. Like many of these hypotheses, a brief paragraph isn’t enough to unpack the thesis.