The art of industrial leapfrogging

Why manufacturing paradigms matter and how to create the next one

This essay is an extended version of the talk I gave at Progress Conference 2025. You can see the recorded talk here.

Note: if you already agree with all the arguments and want to skip to the description of the new paradigm, jump to the section Building a new system.

Manufacturing is like a sewer. We all know it’s important, but we don’t really want to think about it until something goes wrong.

Well, something is going wrong.

If you’re reading this, it means you’re not living under a rock (or at least that your rock-covered home has internet) and therefore you’ve heard some noise about manufacturing. “Reindustrialization”, “onshoring”, “advanced manufacturing”, and other terms are everywhere. Considering that materials and manufacturing underpin civilization, it’s great that such an important and often ignored area is getting the air time it deserves!

But the way that most people are thinking about manufacturing — particularly how to manufacture more things in the US, why that is important, and more generally how centers of manufacturing gravity shift — is incomplete or just plain wrong.

I’m going to unpack a different way to think about manufacturing and how it changes over time: the idea of a manufacturing paradigm.

We’ll dig into the history of manufacturing paradigms, how they shift centers of manufacturing, and explore the fuzzy contours of the new paradigm we might be able to create. Creating this new paradigm is important not just for those of you focused on the US; it’s critical for unlocking human progress both on earth and across the stars.

Manufacturing matters

First, I want to establish some table stakes: Techno-industrial civilization is downstream of manufacturing technology. Regardless of what kind of progress you want to see in the world, you should care about manufacturing.

Do you want to fight disease, improve health, and extend lifespans? You need manufacturing advances. A manufacturing innovation turned penicillin into the life-saving juggernaut that has saved hundreds of millions of lives and arguably helped win WWII: before researchers figured out how to grow huge batches of penicillium rubens in a bioreactor it was a miraculous scientific breakthrough with a worldwide supply of a few hand-made doses. Today, many drugs and medical devices are secretly bottlenecked by their manufacturability.

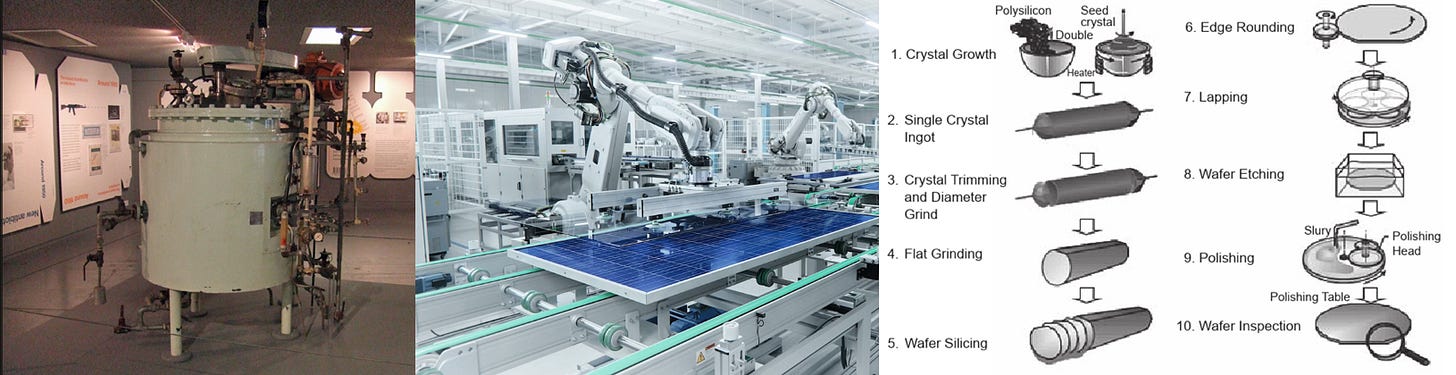

Do you want to prevent climate change, save the environment, and make energy too cheap to meter? You need manufacturing advances. Manufacturing innovations turned solar panels from an obscure technology used only on satellites and toys into one of the cheapest sources of energy at scale. Useful fusion technology secretly hinges on our ability to manufacture easily-replaceable, low-activation material to jacket the inside of fusion reactors and divertor components that can survive sustained 10+ MW/m² heat flux without cracking or becoming brittle.

Do you think all these problems can be solved by AI? You still need manufacturing advances! Repeated manufacturing innovations like the Planar Process are responsible for Moore’s law; we need them to continue in order to improve the physical substrate for AI.

More generally, the impact of any breakthrough is limited if you can’t make enough of it economically. Obviously “enough” and “economically” vary drastically — for LIGO, three gravitational detectors is enough and ~$500M is economical. But if you’re talking about something like a structural material, consumable, or widget, impact requires manufacturing hundreds of thousands of kilograms or units, often for cents per kg or unit.

I can’t count the times that I’ve reached out the author after reading a paper about an exciting breakthrough that can, for example, efficiently pull clean water out of thin air; I ask excitedly “what are the next steps? What would it take to get this thing out in the world so it can deliver on its promise?!” Only to have them give me a funny look and say “oh, we’ve moved on after we published – you could never make huge amounts of it because it would be too expensive/the process will never scale/etc.”

Manufacturing advances often stand between us and unlocking the future

For something so important, we don’t have great theories on how manufacturing progress happens. One framework for thinking about it is through paradigm shifts.

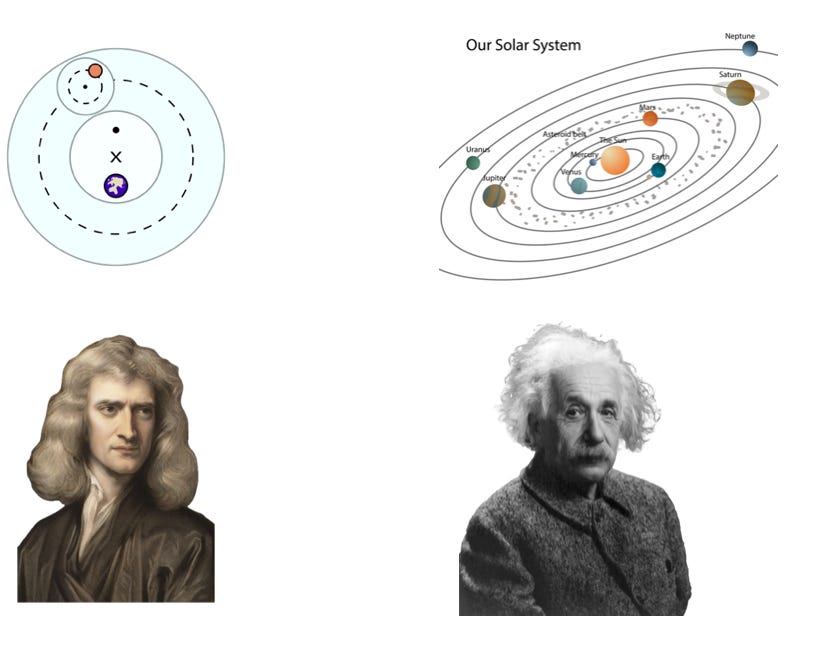

You’re probably familiar with the idea of paradigm shifts in science. Paradigms are the idea (originally from Thomas Kuhn) that there is a set of assumptions and ways of doing things that underpins all the work in a field, and that these foundations are occasionally overturned. The canonical example is the shift from an Earth-centric system of astronomy (where it’s assumed that all the planets and stars revolve around the Earth) to one where the solar system revolves around the sun and the sun is just one star among billions. Another example is the shift from Newtonian mechanics with absolute space and time to Einstein’s paradigm where space and time are observer-dependent.

We can turn this same paradigmatic lens to manufacturing.

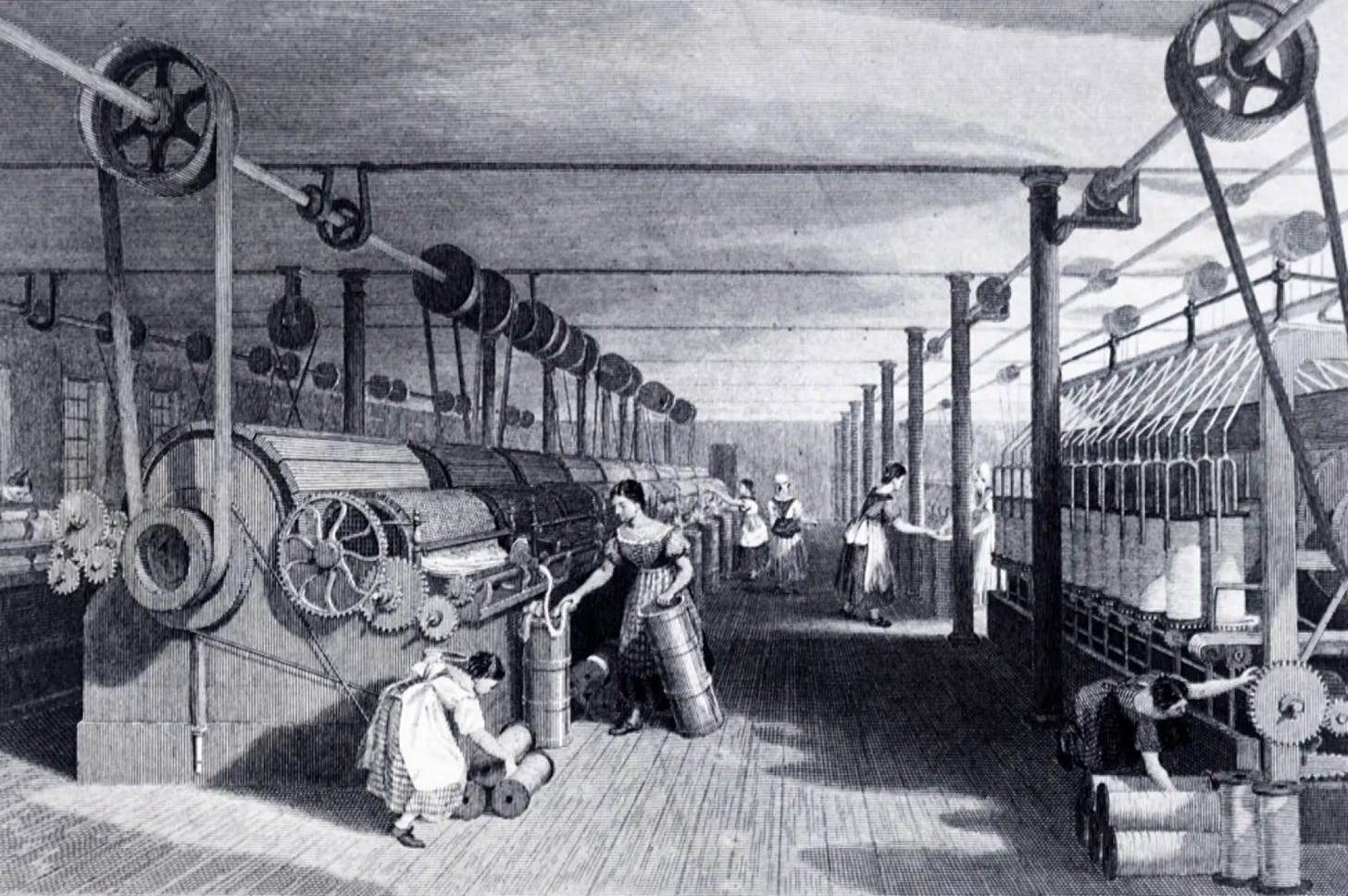

Steam power is a textbook manufacturing paradigm shift. It had obvious effects like new machines, new workflows built around continuously spinning shafts and belts, and new supply chains to create and supply fuel, supplies, and machines. But it also created second-order effects like reorganizing industry and society around factories and manufacturing centers; previously manufacturing was far more distributed, happening in people’s homes and small workshops. Steam power didn’t just make existing products cheaper – it unlocked previously impossible capabilities: rolled steel at scale, precision-machined parts, and continuously processed chemicals.

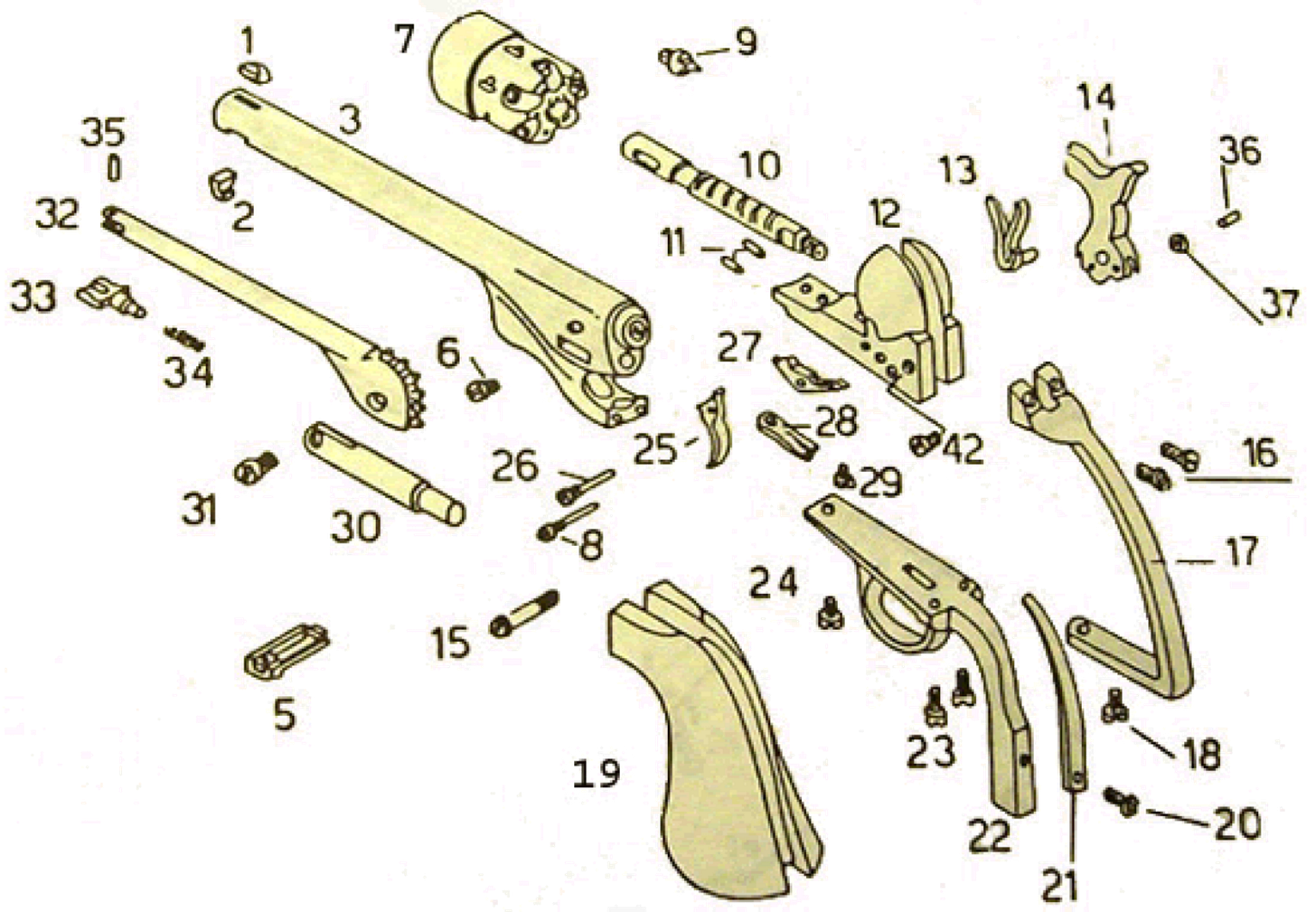

Interchangeable parts were another major paradigm shift. Instead of each part in a gun or sewing machine being hand-filed to fit with each other part in that specific device, precision machinery and fixtures enabled a system where a part from one device could be used in any other device. Like steam, interchangeable parts changed manufacturing equipment, ushering in higher-precision machines and jigs. Workflows shifted: instead of one person doing several production steps and making sure each part fit with the others, now you could have workers doing a single task. Even industrial organization changed: if you can guarantee that a part will fit in an assembly, you don’t need to make all the parts in the same place. More firms can specialize in creating specific components. Interchangeable parts also unlocked products whose complexity would have made them unmaintainable otherwise: from typewriters to bicycles to automobiles.

The current manufacturing paradigm doesn’t have a catchy name like “steam” or “interchangeable parts”, but I like to call it “network manufacturing.” It’s the system enabled by a combination of global containerized shipping, just-in-time manufacturing, and the ability to send information across the world instantaneously. “Designed in California, Made in China” is emblematic of network manufacturing, which enables deep decoupling between the design and manufacturing of a product. Under this paradigm, industrial organization is both global and tiered: cobalt mined in the DRC might be refined in China, processed in Japan, integrated into a chip in Taiwan that is assembled into a phone in India, all according to a design created in the US.

Paradigm Shifts Drive Progress

Not only is manufacturing critical for progress, but so are paradigm shifts in manufacturing.

The first-order effect of paradigm shifts is to decrease prices, which gives more people access to things that were once reserved only for the rich. Mirrors, cotton clothing, and steel cutlery were all once a luxury but are now functionally free. In the same way that new scientific paradigms move us towards a “truer” understanding of the universe, manufacturing paradigms drive the cost of goods towards the raw cost of their material inputs.

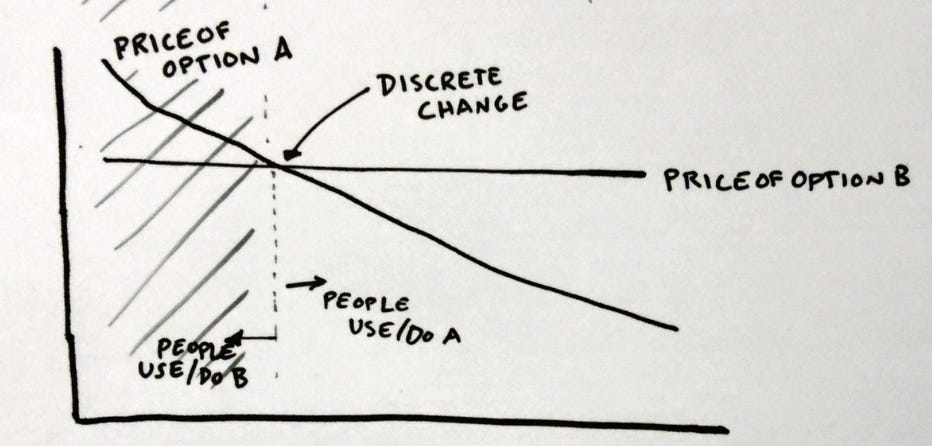

Beyond increasing access, decreasing costs can cause discrete “phase-changes” thanks to thresholding effects. Once LEDs became cheaper than incandescent bulbs, the world quickly switched over, drastically reducing the amount of energy used for lighting and further driving down the cost of LEDs which then could be used for many more applications. The same happened for aluminum, electric-motor-driven tools, digital cameras, solid-state hard drives, and thousands of other technologies.

But the biggest way that paradigm shifts drive progress has nothing to do with cost. It’s how they open up design space and enable us to create things that were impossible no matter how much money you threw at them.

Steam’s consistent power output made possible uniform rails, swung forging hammers far heavier than any person could move, and powered control systems for chemical reactors that could perform the same reactions consistently. These capabilities were, in turn, key enablers for the railroads that drastically improved lives by transporting people and goods, the chemical industry that helped feed the world, and the stainless steel used in so much medical technology.

Ultimately, the precision driven by interchangeable parts unlocked things like turbines, whose blades spin at 10000 RPM mere millimeters from their casing. Interchangeable parts made complex products dependable. Without interchangeable parts, if you didn’t personally know someone who could make a new component by hand (like the handle for a shovel) you were out of luck if something broke. Even if someone could make a car by hand, it would instantly become scrap when any single component broke. Electricity generation would be impossible without the turbines unlocked by interchangeable parts and so would the appliances that turn that electricity into saved labor and more comfortable lives.

(I realize I sound like a broken record about how manufacturing technologies’ second-order-effects affect everyday lives but most people have yet to internalize it, so the yelling will continue.)

Paradigm Lifecycles

We’ve established that manufacturing is important for progress, it progresses through paradigms, and that these paradigm shifts themselves are important. But how do manufacturing paradigm shifts actually happen?

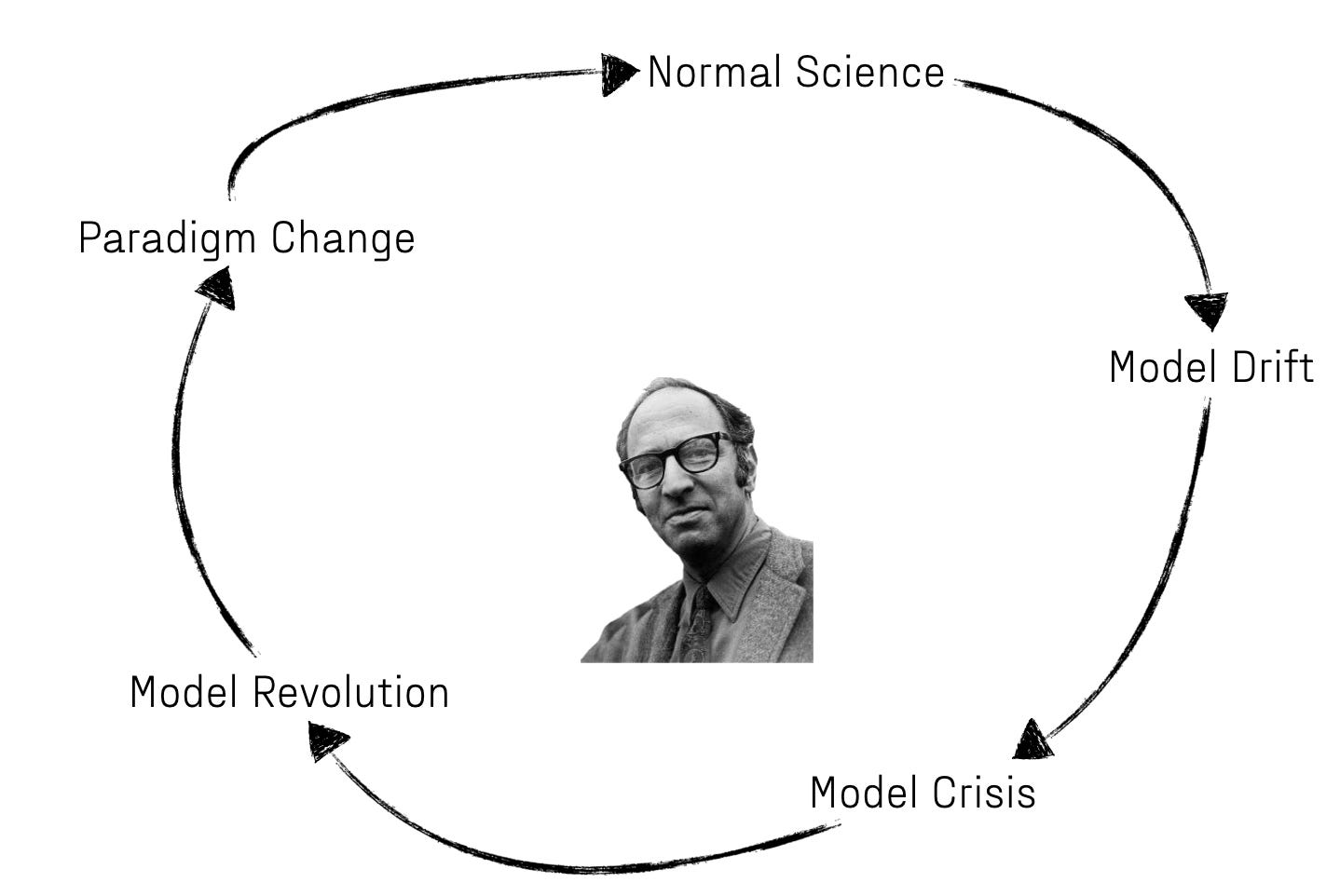

We can think about manufacturing paradigm shifts as a close parallel to “Kuhnsian” scientific paradigm shifts.

Normal Science. Most of the time, science operates under some paradigm (say Earth-centric cosmology). People make new observations (like more precise measurements of Venus’ path through the sky) and explain them through the lens of that paradigm (“well, guess we need to add some more epicycles to explain the Venusian path, there must be some more revolving crystal spheres than we thought.”)

Model Drift. Over time, observations pile up that are hard to explain within the existing paradigm: how does Venus have phases if it’s always on the opposite side of the earth from the sun? How does Jupiter have moons? If stars are holes in a celestial sphere, why do they have different brightnesses and sizes? Why are there so many freaking epicycles???

Model Crisis. Eventually, people like Copernicus and Galileo realize that perhaps the whole thing is wrong or incomplete. (Spoiler alert: this may be where we are in manufacturing right now.)

Model Revolution. Going beyond just pointing out the flaws in the old paradigm, innovators propose a new paradigm, like the heliocentric model of the solar system. Massive fights break out as people defend against ideas that, if right, threaten their careers, identities, and worldviews. Notably, new paradigms often have huge gaps themselves, so the better paradigm is not a cut and dry affair. These fights can last for decades.

Paradigm change. Eventually, the new paradigm reaches a consensus tipping point — in the case of the heliocentric solar system, most people would point to the theory of gravity which provided a simple, consistent explanation for all observations to that time and had a lot of predictive power.

Normal science. The cycle begins anew. Science never gives us the ultimate truth, but merely creates ever-more-correct models of the universe. Newtonian mechanics are eventually subsumed by general relativity, which has its own paradigmatic holes waiting to be filled.

(Let’s caveat that this is an obscenely stylized description of how the world works and an extremely abbreviated description of the obscenely stylized description! A lot of science proceeds without paradigm shifts. You can have multiple overlapping paradigms at the same time. Many proposed new paradigms are just wrong.)

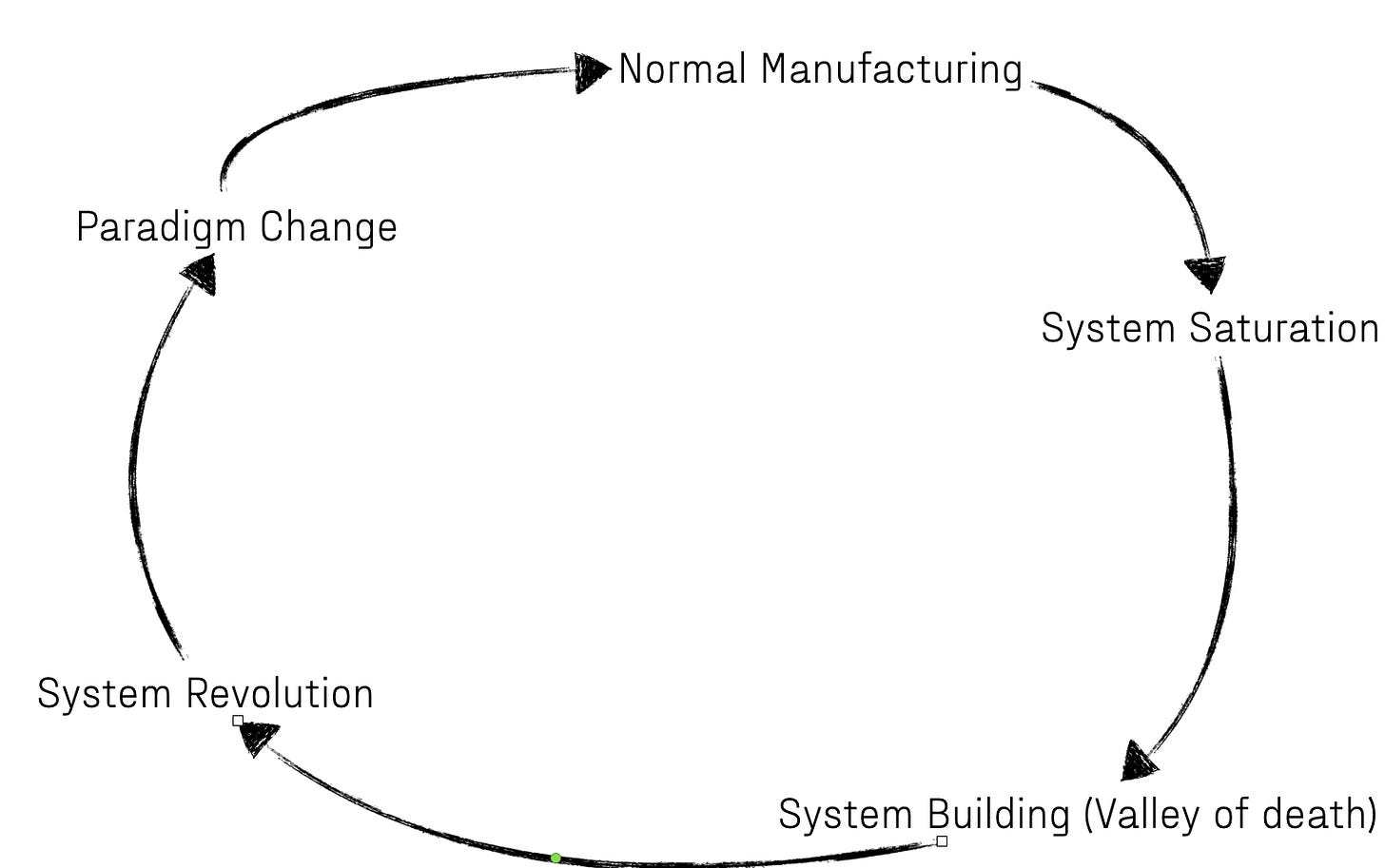

The analogous cycle in manufacturing paradigms looks like:

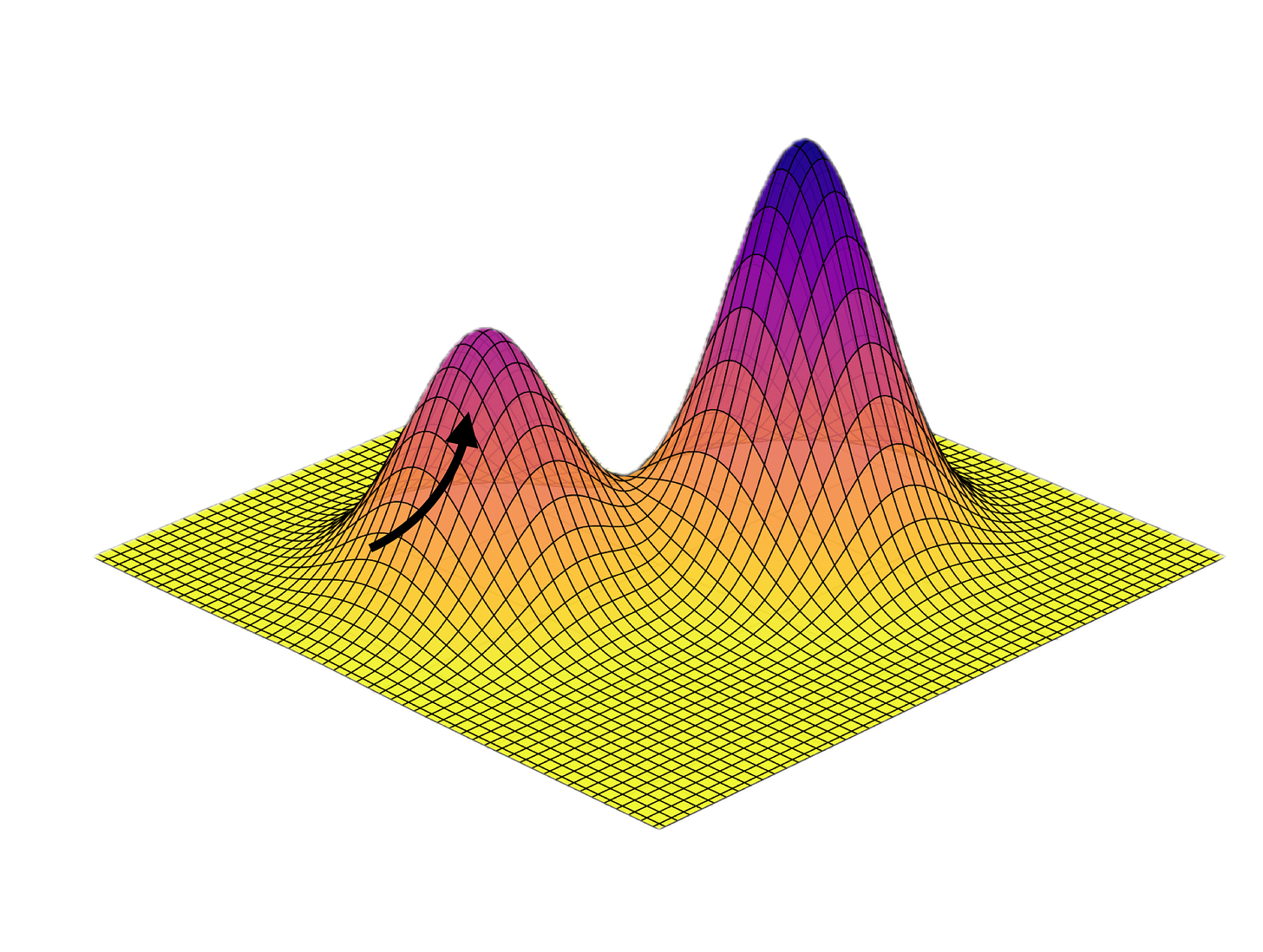

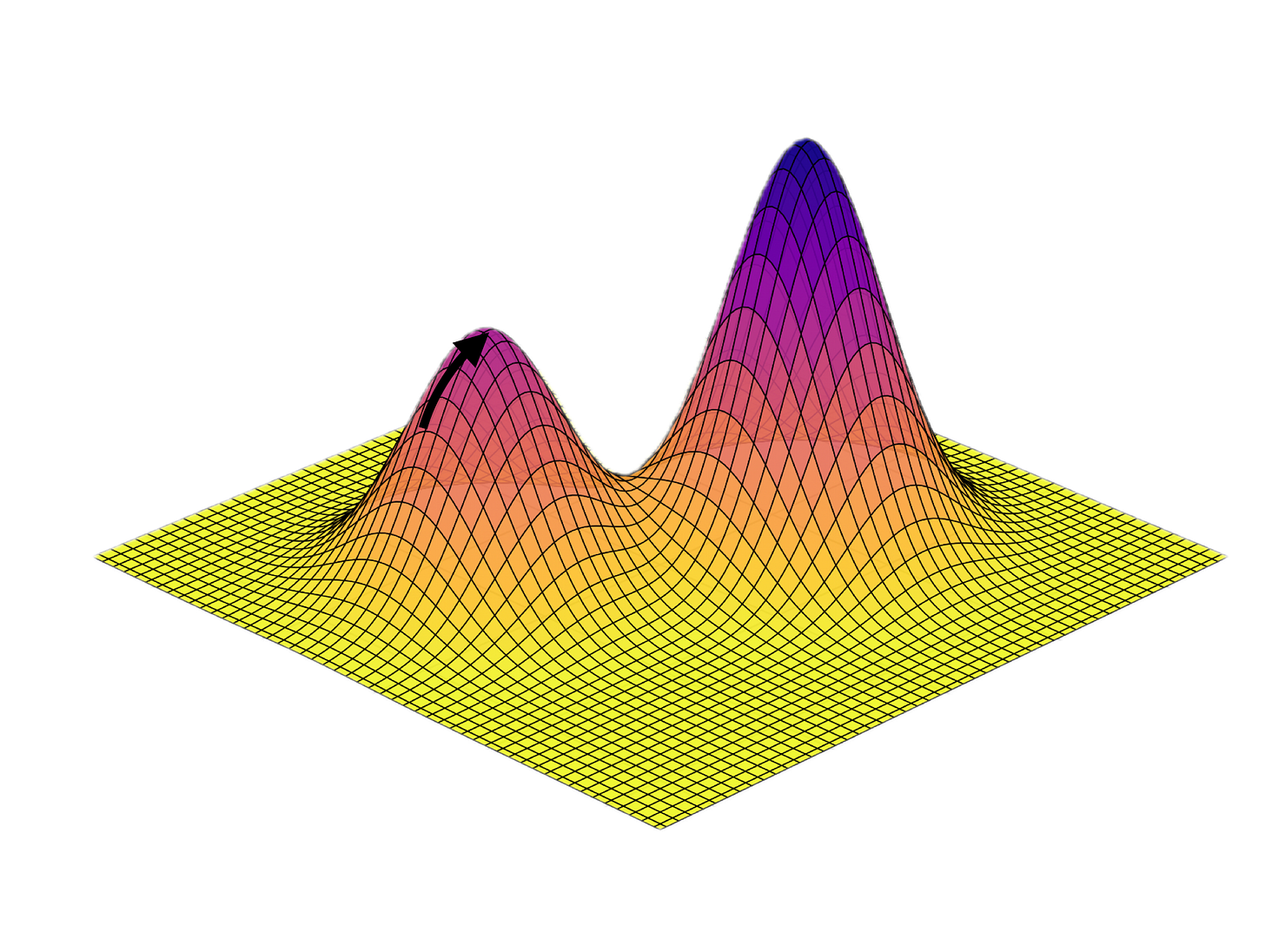

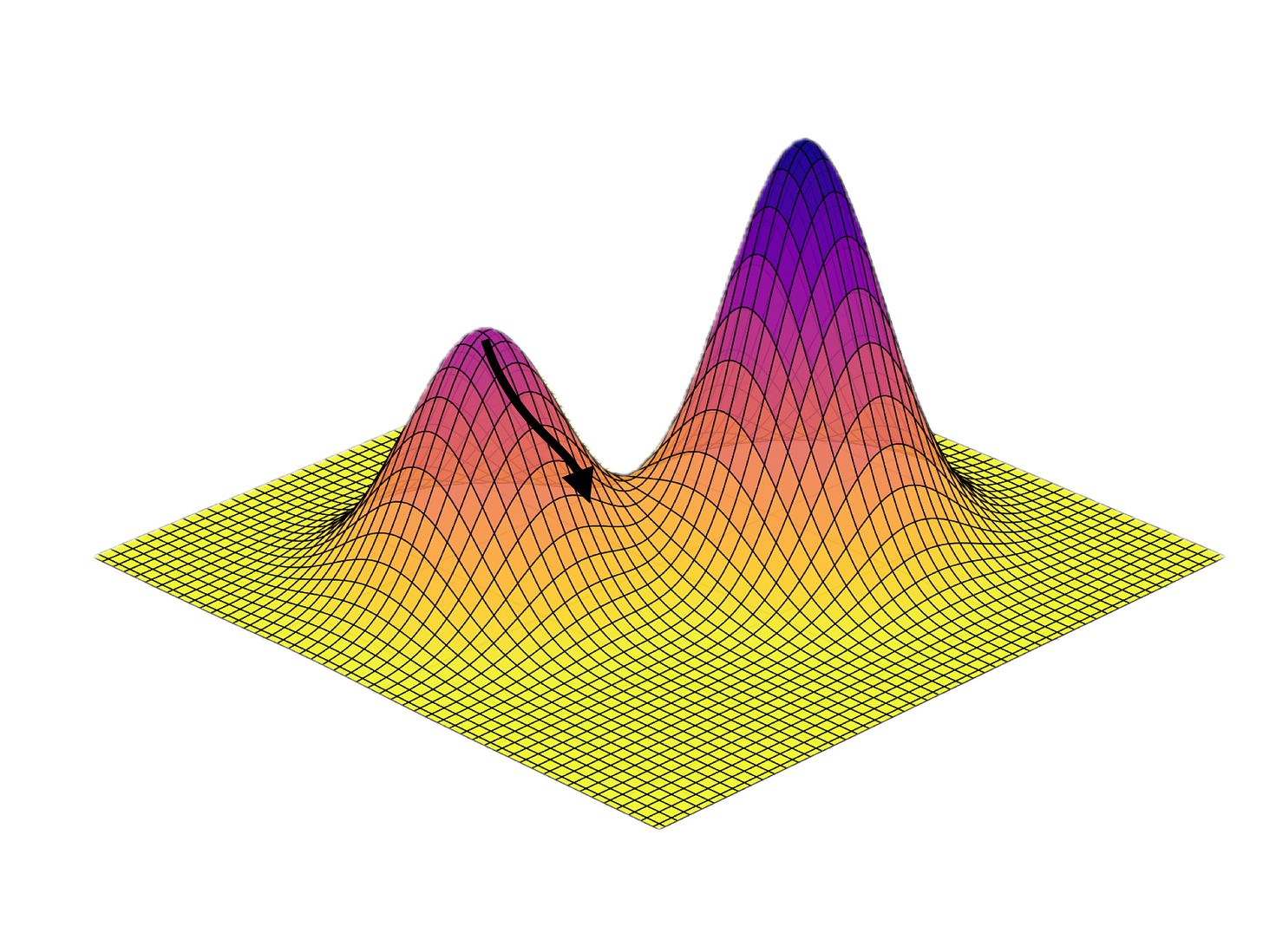

Normal Manufacturing. Most of the time, manufacturing progresses when process innovations improve systems, making things faster and more efficient. You can think of a manufacturing paradigm as a high-dimensional hill that we climb as we optimize more of the components of that system. If you’ve read Brian Potter’s book The Origins of Efficiency, most of it deals with this world. (And if you haven’t read it, you should!)

System Saturation. Eventually, it becomes harder and harder to eke out more efficiency gains within a given paradigm. You reach the top of the hill as you make the best steam-powered looms, the largest factories, and the most complex supply chains you can get away with.

System Building. Some people begin building components, processes, and nascent systems that are anti-paradigmatic. These things are poor fits for the current paradigm and often create products that are more expensive or poorer quality than the ones the existing paradigm creates or simply have no place in standard workflows. For years, guns made with interchangeable parts were both more expensive and lower quality than their hand-crafted counterparts. The early products of mechanized looms were lower quality than hand-woven counterparts. (And even today people prize hand-woven rugs.) Today, 3D printers are consistently criticized for their surface finish and impracticality for making huge numbers of the same thing.

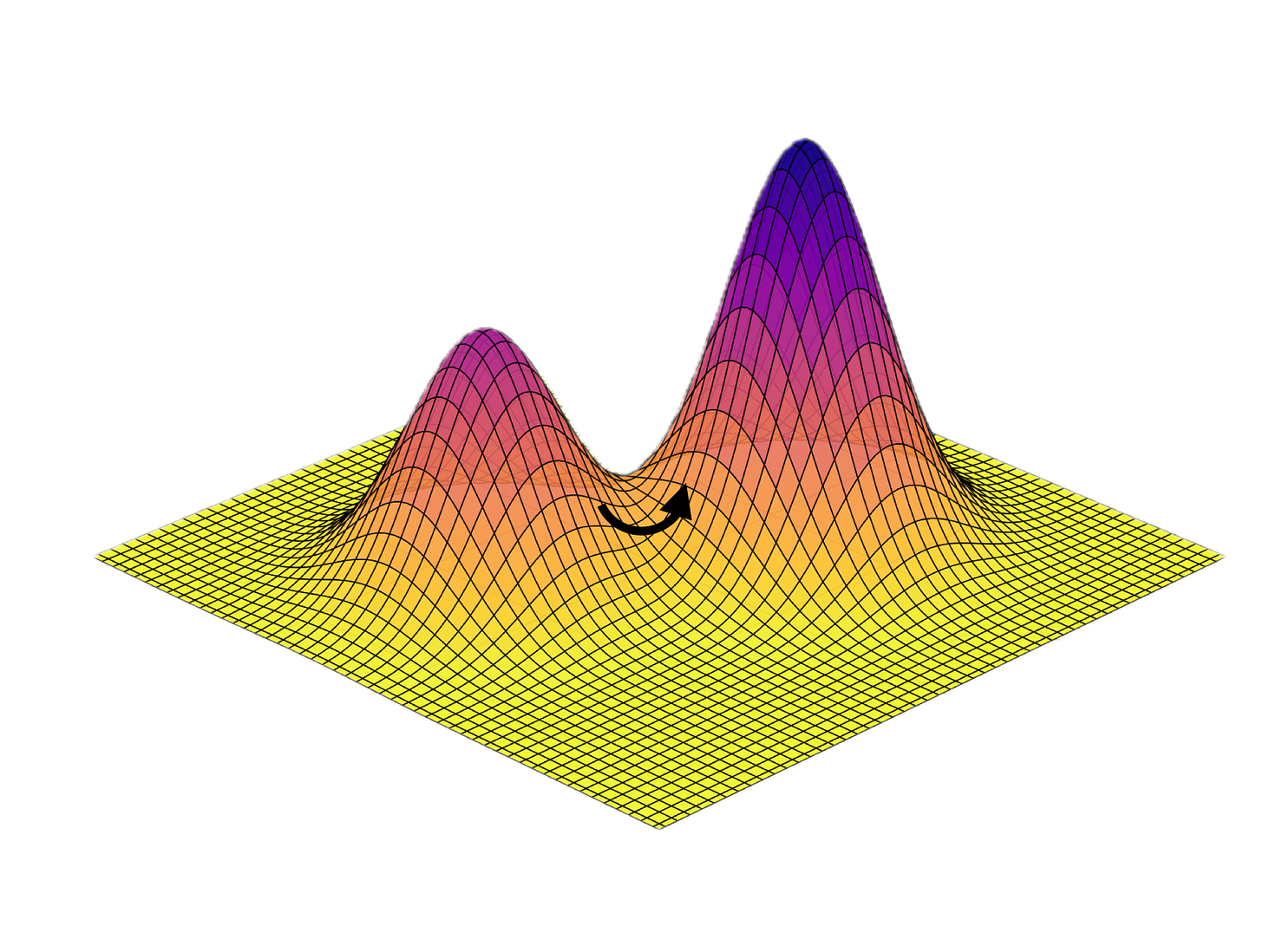

System Revolution. If you’ve heard of “the Valley of Death,” that’s stage four for manufacturing paradigms: building them out requires a ton of resources, time, and work without any sort of inevitability. Lucky systems find a niche that values their capabilities enough to tolerate the downsides: interchangeable parts were valuable enough on the battlefield that the US military was willing to support the incremental improvements to the system.

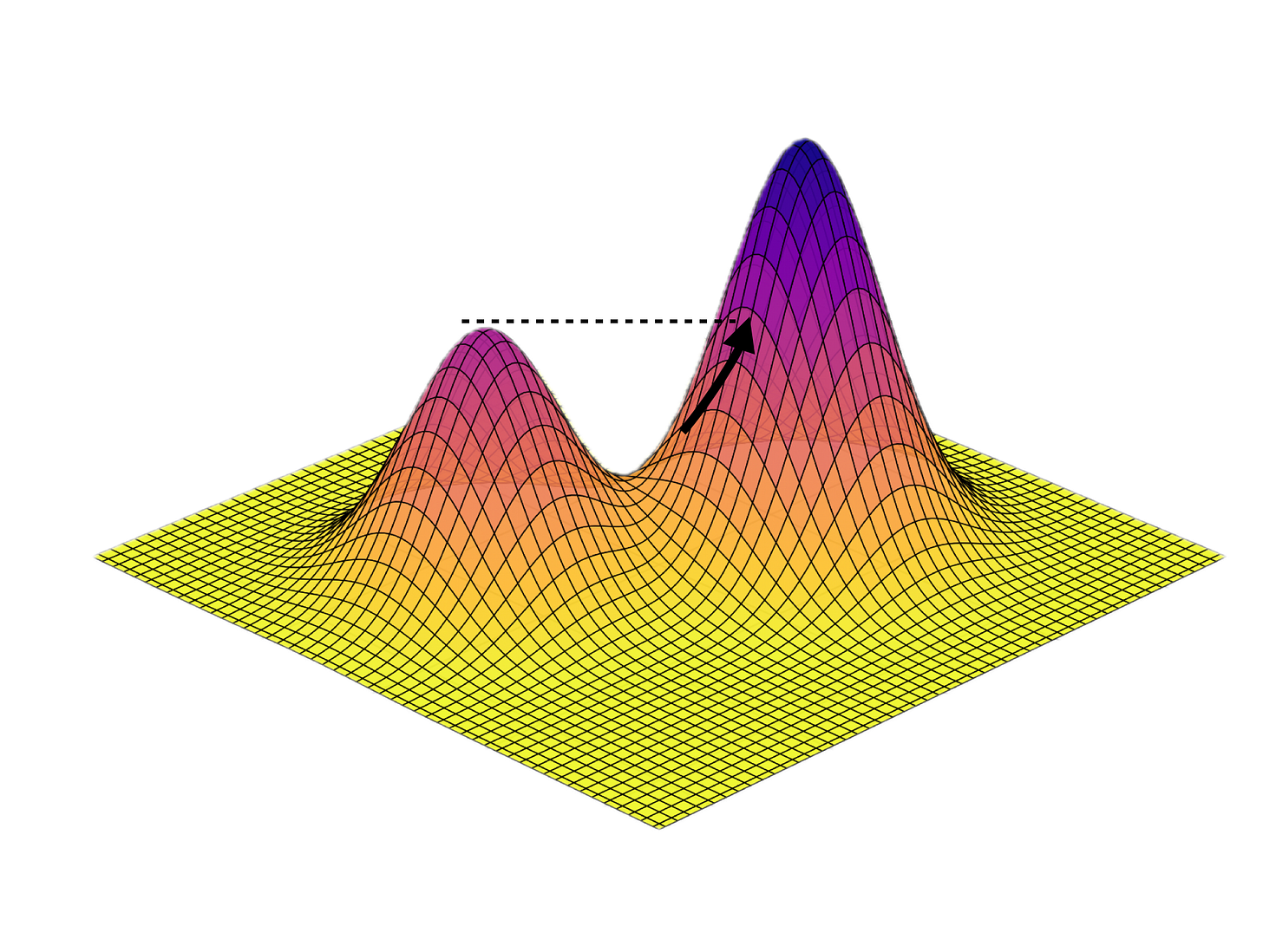

Paradigm Change. Eventually, crawling up a new hill finally produces outputs that surpass existing paradigms on enough dimensions to create a cascading shift: as more manufacturers switch over to the new system (or new manufacturers using the new system outcompete the old ones using the old system) the trajectory accelerates and the new paradigm becomes the normal ones.

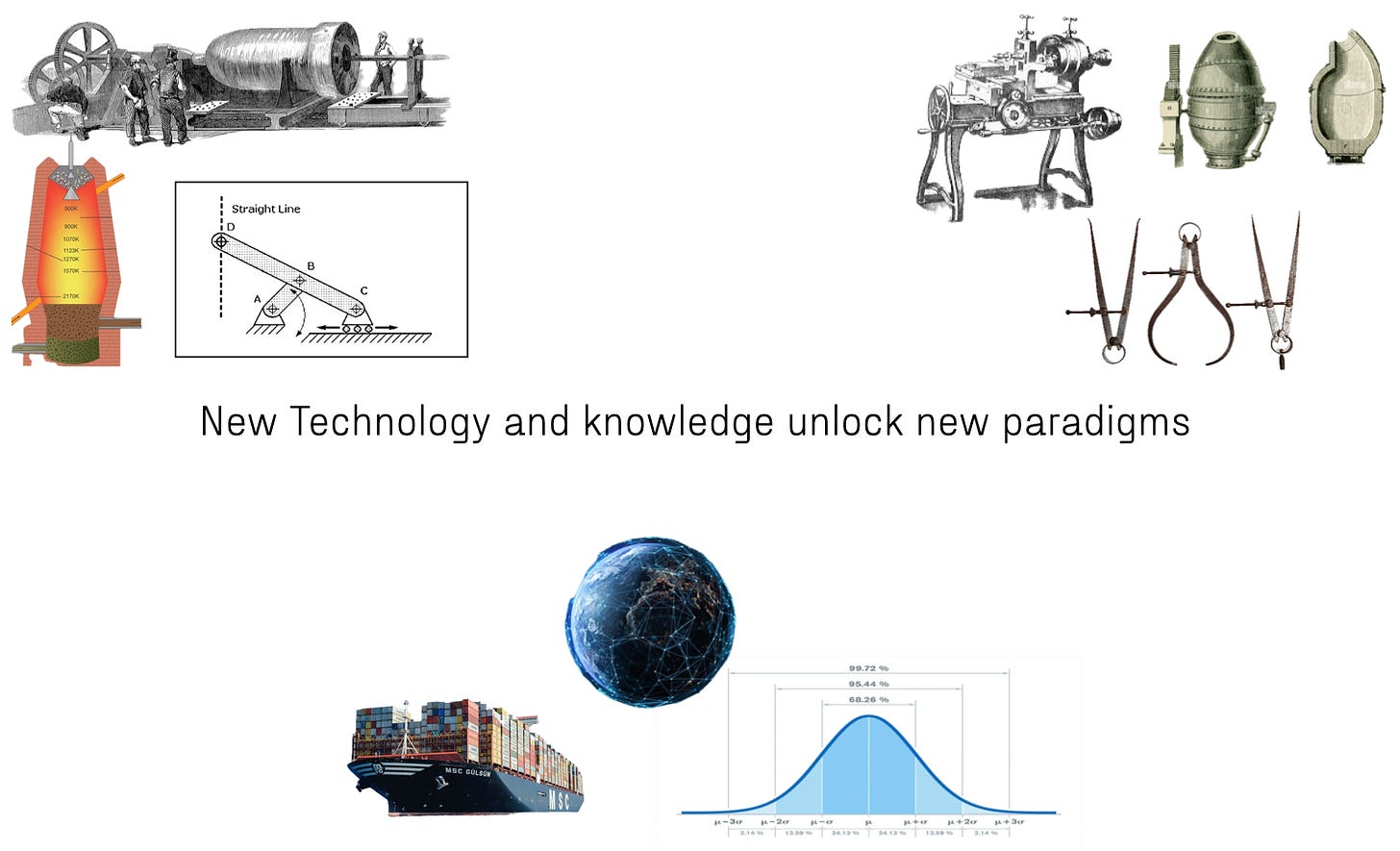

New technology and knowledge unlock new paradigms

Another key dynamic of paradigms is that they don’t just spring fully formed out of people’s heads. Henry Ford didn’t just sit down one day and say “well if we’re going to have interchangeable parts on an assembly line we’re going to need a whole system of precision gauges, machine tools, high-quality steel, and the process knowledge to use all of it; welp, better get started!” New technologies and knowledge unlock new paradigms. These prerequisites are almost always created without the full vision of the new paradigm.

Steam powered manufacturing would have been impossible without cylinder boring technologies originally meant for making canons, blast furnaces, or linkages. Interchangeable parts depended on high-quality steel from the Bessemer process, precision machine tools like mills and lathes, and a whole interconnected suite of gauges and other measuring devices that let you determine whether a part is actually within spec.

Today’s network manufacturing is downstream of containerized transport drastically lowering international shipping costs, a mastery of statistics that enables just-in-time systems to hunt down and eliminate production bottlenecks, and of course, the internet (and the infrastructure behind it) that makes information transfer practically instantaneous and free.

New manufacturing paradigms are impossible without a thousand other projects that go on below the surface. These enabling technologies are always developed for other reasons. New paradigms need people who are close enough to manufacturing to notice what’s newly possible — and who have slack to explore it.

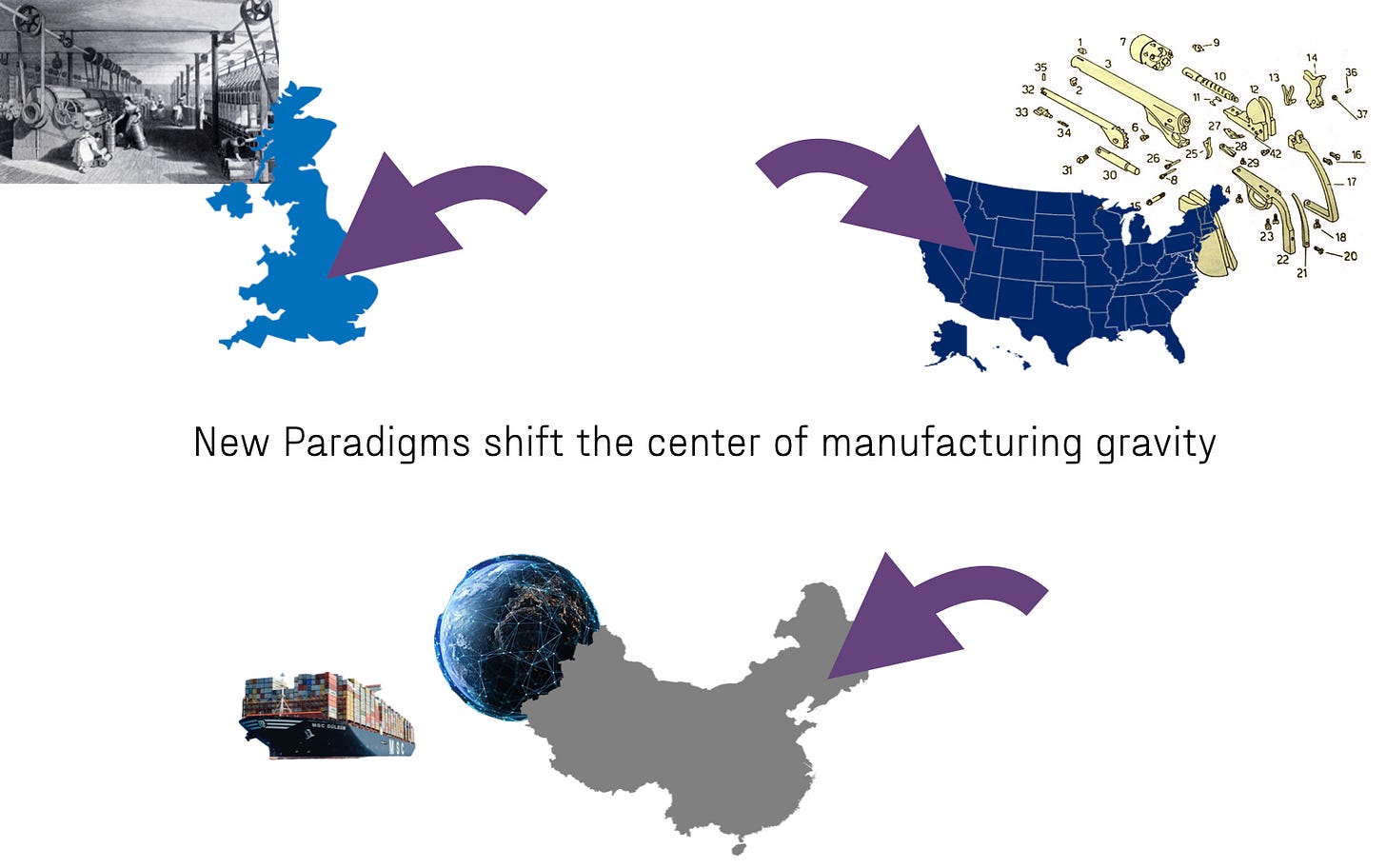

New paradigms shift the center of manufacturing gravity

New paradigms alter the geography of the manufacturing landscape. Britain was a manufacturing backwater before steam power made it into a manufacturing powerhouse in the 18th century. Observers of the 1851 Great Exhibition in London wrote about the American products dismissively before “The American System” (which was the term for interchangeable parts at the time) catapulted the US into manufacturing dominance. The same pattern holds for Germany and chemical engineering, Japan and just-in-time manufacturing, and of course, China and network manufacturing. The places that develop the process knowledge around a new paradigm are able to race up the new slope.

Notably, new manufacturing paradigms almost always come from places that are not manufacturing leaders. It’s a straightforward innovator’s dilemma explanation: when you dominate a particular paradigm, mindsets, infrastructure, and workflows all point towards pushing further and further up the existing hill. Put a bookmark here, because it will be relevant in just a bit.

Building a new system

A final property of manufacturing paradigms (and paradigms in general) is that they look both inevitable in retrospect and unchangeable in the present. Looking back, it’s obvious that interchangeable parts were a good idea. Using cheap shipping to take advantage of specialization, trade, and scale is just economics 101. Looking forward, it’s incredibly hard to imagine things being fundamentally different: when most people say “advanced manufacturing” they mean automating what we’re already doing and figuring out how to scale up things that haven’t already been scaled.

Paradigms look unchangeable until they shift.

A new manufacturing paradigm is possible. The old system is full of epicycles and inconsistent observations are starting to pile up.

The epicycles are clear. The current paradigm relies on incredibly efficient but incredibly fragile supply chains. One shock can ripple through the system, creating shortages and cost spikes for years. It incentivizes cheap products that are meant to be thrown away instead of repaired or modified. The only things worth making are those that can be sold at massive scale. Entire industries rely on inputs from a single country, or even a single factory.

Let’s be clear: the system has delivered massive benefits to billions of people. But Newton’s physics was able to account for every observation for hundreds of years. That didn’t mean that Einstein couldn’t unlock a torrent of new discoveries.

We can put today’s piling-up observations into four buckets:

Leveraging new phenomena

Sensors and compute

Tooling-free processes

Launch and Space

Leveraging new phenomena. Near the end of the 20th century, humanity upgraded our ability to harness a handful of natural phenomena, but we still haven’t gotten anywhere near using them to their full potential. The most obvious three are lasers, magnets, and the photovoltaic effect. Lasers can (among many other things) create nano-scale structures, heat things precisely at a distance, and slice through material with exquisite precision. Powerful magnets (of both the rare-earth and superconducting sort) can move things without physical contact, weld unweldable metals, and create otherwise-impossible actuators. (Actuator is a fancy word for a generic thing that a machine uses to physically act on the world — anything from a robotic hand to a leaf blower can be an actuator.) Everybody knows about solar, but our manufacturing systems haven’t adapted at all to an energy source that is effectively free for part of the day but off the rest of it.

Sensors and compute. You may have noticed that computers have gotten way better. They can model and simulate almost anything, control systems in real time, and a host of other fancy things. And yet, by and large we’ve used them to improve existing parts of the manufacturing system rather than building new systems around their capabilities. Yes, I’m finally talking about AI (thank you to those of you who have read this far despite its absence). Sensors that let the computers know what’s actually going on have also improved dramatically.

Tooling-free processes. To make something at scale today, you first need to spend a lot of time and effort making the things to make the things. These are the custom-made casts, dies, and a plethora of specialized machines collectively known as “tooling.” There are an ever increasing number of “tooling-free” processes that can make different things without needing to swap out any physical components: 3D printers, laser cutters, EDM cutters, and more. These machines are criticized within the existing paradigm because they can’t produce identical components at scale as quickly or efficiently as tooled system. That kind of criticism is often a tell for the roots of a new paradigm.

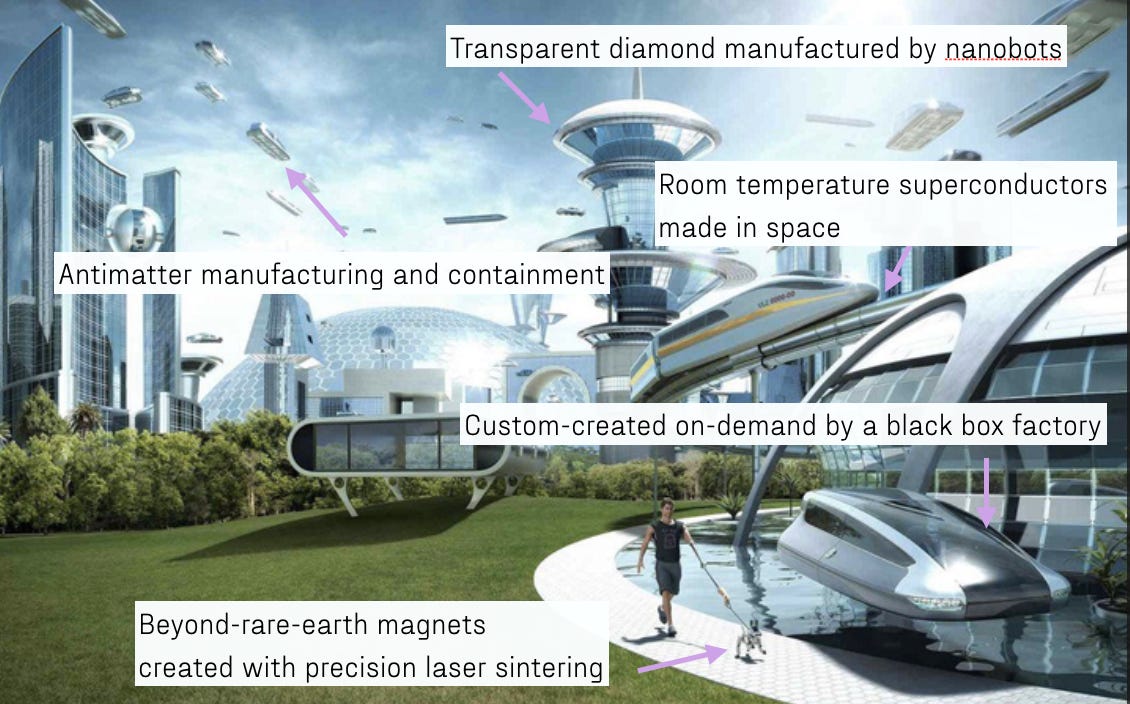

Launch costs and space. This is the most speculative one. The cost of launching mass into orbit (and bringing it back) is decreasing while the number of things people want to do in space are increasing (I will not weigh in on orbital datacenters here). You can manufacture things in space that you cannot on Earth thanks to zero-gravity, infinite vacuum, and extremely low temperatures (if you can dump heat effectively). Obvious examples are things like fiber optics that need extremely large and pure crystals but in reality, we haven’t scratched the surface. Space lets you avoid many of the annoying things that manufacturers work very hard to deal with on Earth: material doesn’t settle so it can mix evenly, it’s easy to keep reactive material from touching the walls of a container, and you can create massive films without them tearing.

All four of these buckets are coupled, bear with me.

A quick aside on AI: You might be asking — “Ben, isn’t the next manufacturing paradigm obvious? It’s just AI. Won’t we just have lights-out factories full of humanoid robots making stuff? It’s already happening and this whole piece is just irrelevant navel-gazing."

But automation on its own does not cause paradigm shifts! “Raw” automation just makes existing paradigms more efficient (or doesn’t). We have been automating more and more pieces of the manufacturing process since the punch-card directed power loom in 1805. New paradigms require large clusters of enabling technologies and new systems built around them. The historical pattern suggests that AI may certainly be a piece of the puzzle, but it’s not the whole picture.

(Of course, there is no way to make yourself seem more foolish than to try to predict the future so I could be totally wrong here and humanoid robots could create a cascade of systemic changes that utterly transform how things are made. But I have my doubts.)

What does this new paradigm look like?

It’s incredibly hard to describe in the abstract a paradigm that does not yet exist and whose specifics depend heavily on work that has not yet been done. I’m not a great science fiction writer, but I’m going to attempt to paint some pictures of what a world with this new paradigm might look like before describing it more abstractly.

Low-effective-scale cells. Jane is an engineer at Tesla with a brilliant idea about how to make electric cars that, among other things, are powered by supercapacitors and take advantage of a new type of magnet; both of these new systems require reinventing how to make a car from the ground up. She builds a prototype using a heavily-instrumented “cell” that looks kind of like a shipping crate filled with different machines that can change what they make on the fly — think the hybrid offspring of 5-axis CNCs, 3D printers, laser cutters, and their ilk. She sells the first prototype to a millionaire with a personal racetrack and uses that money to build two more of the vehicles — a seamless process because the cell is able to replicate and improve on the exact steps she used to make the prototype using its own actuators. Selling these vehicles gives her enough evidence to get a new form of technology loan to lease several identical scales that let her start scaling production by parallelizing a continuously improving process as the cells learn from each other. This whole process is aided by new forms of regulations that use the digitized design and process data to automatically sign off on the new technology.

Rapidly reconfigurable manufacturing. COVID-37 strikes; but because the now-large car company is using this modular manufacturing technology that doesn’t require a pile of specialized machines and tooling like the current paradigm, it’s able to quickly switch production to start making masks and other gear. (The same thing is true when it needs to switch production over to microsubs during the war of ‘39.)

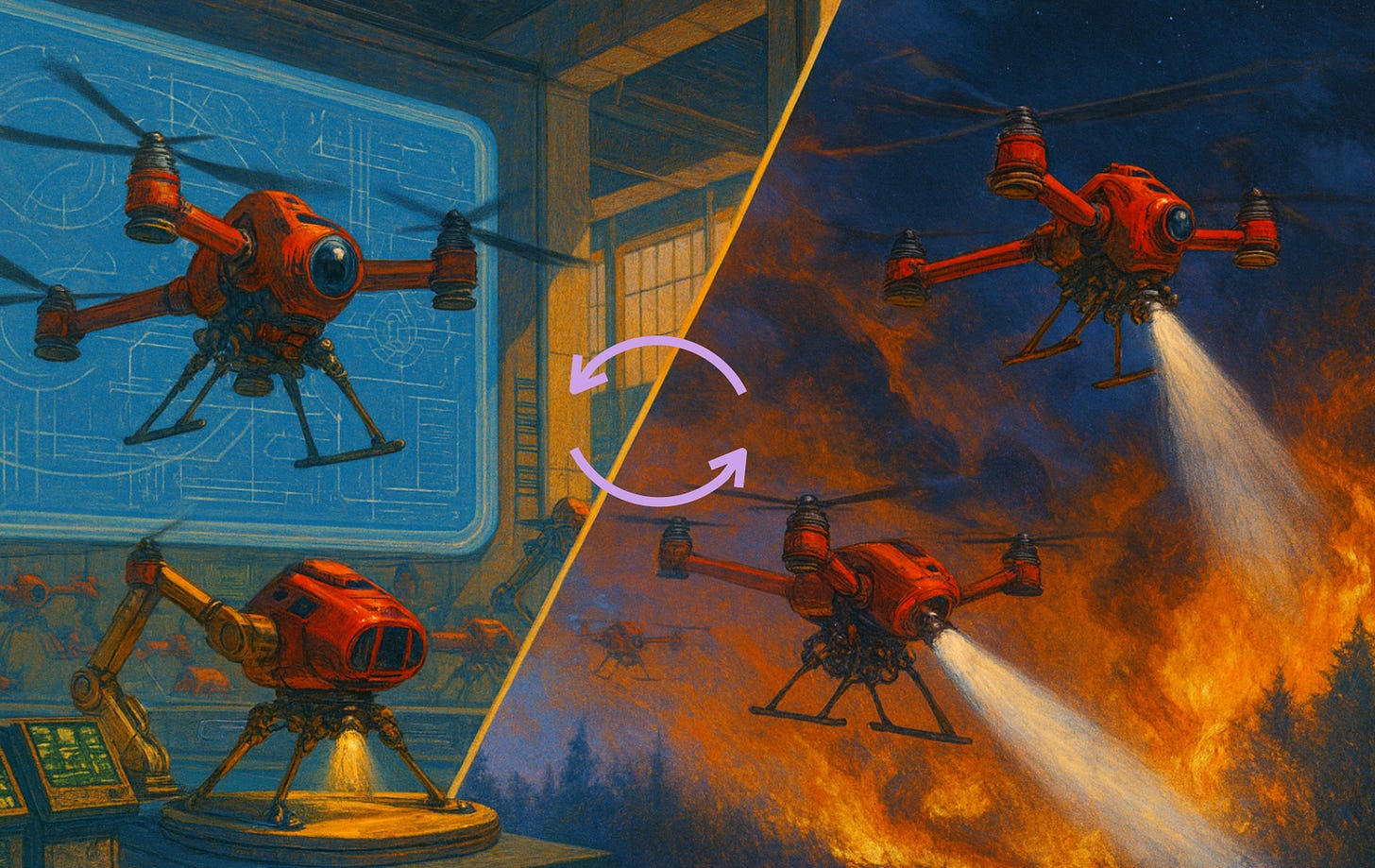

Closed-loop manufacturing. A different division of the company produces fire-fighting drones. Data from drones rolling out of final assembly cells feeding back into its design to continuously remove defects and improve production efficiency. More importantly, telemetry from the field shows that smoke is causing unexpected degradation in the motors (that use a new kind magnet made out of directional printed iron crystals that outperforms rare earths). That data both triggers immediate short-term design fixes and kicks off a project in the R&D department that both finds the root cause of the problem and unexpectedly discovers a new alloy that could give flying cars a 300 mile range.

Space manufacturing. Awkwardly, that alloy that can only be made at scale in zero-g, high-vacuum environments (ie. space). Luckily, cell-based modular manufacturing makes it so that Daniel can prototype the process on the ground and then instantly implement it in a twin cell in orbit instead of waiting a year for a launch slot for each iteration. His friends in the pharma industry use a similar process to discover and make miracle drugs.

The abstract pieces of the paradigm, as I see them, are the following;

Modular, composable cells that leverage new kinds of tools and automated actuators to make it fast to iterate on designs, scale through parallelization, and quickly change what they make.

Closed loops between the product’s design, the manufacturing process, the final products, and how they work in the field.

The cells make it so that the minimum viable efficient scale for manufacturing drastically decreases and makes manufacturing much more location agnostic. You can drop a small “factory” outside of most major cities and propagate process improvements across all of them simultaneously.

The remotely reconfigurable, low-minimum efficient scale, and lower-infrastructure-intensity cells and feedback loops enable space manufacturing. (Except for the hard-to-get-things-up-there-and-back-down nature of space, it’s actually a great place to manufacture things — chemicals don’t settle, you don’t have to worry about environmental damage, there are no contaminants, and much more.)

We’ve already reached this paradigms’ copernican era — there are many tools and processes that show cracks in the current paradigm and hint at the new one. 3D printers are starting to get good enough that there are a few products that it makes sense to scale up through massive printer farms. Tooling-free systems like laser cutters, electrical discharge machines, and automated metal breaks keep improving. Places like Machina Labs are creating new tooling-free systems. Sensors are getting cheaper and rudimentary “digital twin” systems are coming into their own. But right now all of these things are like new astronomical observations that we’re still trying to create paradigmatic epicycles around.

I realize that description needs far more detail! Filling out those details requires a lot of work, both back-of-the-envelope roadmapping and empirical tinkering that I am actively working to aggregate the time, resources, and people for (you’re welcome to help).

Why you should care

Even if you have no intrinsic interest in manufacturing, you should care about creating this new paradigm.

If you care about US power you should want the United States to be a place where people make things. (I’ll get to why you should want that even if you’re a globalist.) Many people claim to want this, but we’re going about it wrong. We’re not going to manufacture things cost-effectively in the US by putting up tariffs, doing top-down industrial policy, and otherwise trying to out-China China. Even ignoring their heavy government subsidies, China has gone too far down the learning curves of conventional ways of manufacturing things. History shows us that the way to shift manufacturing centers of gravity is by creating new paradigms.

If you care about humanity, could care less where things are made, and just want a flourishing future, you should still care about creating a new manufacturing paradigm in the US. The history of manufacturing paradigms (and Schumpeterian disruption theory) has shown us that radically new paradigms need to come from places that do not currently dominate manufacturing. Incumbents have the most reason to avoid the long, painful process of going down into the valley of death between the current optima and the next. So if you want the trends that have lifted billions out of poverty to continue, we need new paradigms, and those paradigms need to come from places that don’t dominate manufacturing.

I care about this for selfish reasons. I want to live in the place that unlocks the future.

There are too many stories to ignore of how important it was for great innovation orgs like Bell Labs or Skunkworks to have people with deep manufacturing experience in the room. Not only did they enable rapid feedback loops between idea and physical prototype, but they made sure that the eventual output was manufacturable (remember, inventions are ultimately useless if you can’t make enough of them economically). On top of all that, tacit manufacturing process knowledge is often critical to invention itself. One of the bottlenecks to creating the transistor was bonding a metal whisker to germanium without destroying it; the problem was solved by a machinist, John Saby, who applied a trick for manufacturing precision radio components — evaporating a thin sheet of gold onto mica, slitting it, and then pressing the gold-mica slab onto the germanium so that the stress caused two gold whisker contacts to squeeze through the mica.

I’ve belabored the point about organizations because the deep coupling between invention and manufacturing also exists at a regional level. Innovation is incredibly sensitive to friction; there is a huge difference between a world where you can run ideas by your machinist neighbor over the fence, walk through a giant components market on your way home from work, or drive over to five different specialized machine shops and one in which you cannot.

Hobbyists and tinkerers are a secret vanguard of innovation. The Homebrew Computer Club, early rocketry and aviation, drones, radios, and the list goes on. But these people thrive on discarded equipment and tools, skills they gleaned from work and their community, and borrowed infrastructure.

Furthermore, what you know how to do, and think is possible, deeply affects the kind of ideas you come up with. When everybody is just doing software, you come up with new ideas for software. When everybody is writing blogs, you come up with great essay ideas. When you make physical things and everybody around you is too, you come up with ideas for physical things. Unless you want a Ready-Player-One-WALL-E-Matrix future, the place that unlocks the future is going to be the place that comes up with brilliant ideas for physical technology and implements them.

New Paradigms Are Not Inevitable

After seeing the cracks in an old paradigm and possibilities for a new one, it’s easy to think that all we need to do is sit back, maybe invest in a few startups, and let the unstoppable march of progress do its thing. This couldn’t be farther from the truth.

New paradigms are not inevitable. Creating them requires swallowing three bitter pills that are especially at odds with our current moment.

First, new paradigms take time. Eli Whitney won the first contract to produce muskets with interchangeable parts in 1798, but the system wasn’t in widespread use until the 1870s. Steam-powered manufacturing took almost 60 years to catch on in 19th century Britain. Things move slightly faster now, but just-in-time-manufacturing still took several decades to emerge in Japan, and the same is true for the network system in China. These decades-long timescales are a poor fit both for most contemporary forms of capital and political timescales.

Second, new paradigms are not politically convenient. Increased productivity means doing more with fewer people; increasing the total amount of manufacturing will not create piles of new jobs nationally, or even where things are being built. It won’t create zero jobs, but if jobs are a political selling point, it will warp the technology to the point of uselessness. Speaking of where things are built, new paradigms like this depend on agglomeration effects in places that are hard to predict a-priori. That means the standard politically expedient moves (in the US) of top-down funding decisions and spreading money around geographically to scratch the right backs are the best ways to make sure nothing useful gets done.

Third, creating new paradigms requires work that doesn’t currently have a home. It requires uncertain work that strives to reinvent entire systems, while simultaneously being laser focused on usefulness. Much of the work that needs to be done in the next five years is distinctly pre-commercial — it does not yet make sense as a rational business investment. Startups need to focus on point changes in existing systems or the product they’re getting out the door. Most manufacturing companies don’t have the margins to stop production even to test a new machine, let alone create a research arm. And the academic system that has a near-monopoly on pre-commercial research is ill-suited to this work for more reasons than we have time for.

These bitter pills mean that without shifting trajectories, I’m pessimistic about this new paradigm’s prospects — despite excitement and money flying around reindustrialization, AI-for-science-and-manufacturing, and hardware startups. But changing those prospects is why I’m writing this and why we’re doing what we’re doing at Speculative Technologies!

Creating new paradigms always rubs people the wrong way and goes against dominant ways of doing things. That includes the government-startup-academia complex in the US.

It may sound odd, but I see creating new manufacturing paradigms as a humanistic endeavor on par with curing cancer, ending poverty, or discovering the secrets of the universe. Without new manufacturing paradigms, progress will grind to a halt; whether you care about progress in health, wealth, or going to the stars. The importance is just under the surface.

Remember, manufacturing is like sewer systems.

Sewers are a miracle, arguably saving hundreds of millions of lives and making life so much more pleasant to boot. But they didn’t just happen by default. It took hard, thankless work by many individuals who captured little of the value they created.

If we have that opportunity to create that kind of progress, shouldn’t we take it?

Very interesting!

Small error in wording: "I’m sanguine about this new paradigm’s prospects, despite excitement and money flying around..."

Not sanguine, but it's opposite, pessimistic.

Is there anyone you know of, or examples you can point to, where people are using no-tooling processes to produce the tooling for standardized processes?