Making BBNs in the 21st century

These are some notes on Eric Gilliam’s recent piece on BBN as a model for new research organizations expanding on notes from a Speculative Technologies lab meeting.

Definitions

Taking the name as given (personally I think a better term might be “frontier research contractor” or something), the piece under-defines what we mean by “a BBN” and in fact, mentions only one organization that fits the pattern that is not BBN itself.

Reading between the lines, here are the criteria I would gesture for a BBN:

A private, mostly-independent organization…

doing research at the frontier of science and technology

that is able to attract top tier talent

funded to some extent (to what extent is an open question) by contracts

that doesn’t follow normal academic research structures

We do need new BBNs

While a lot of this response will sound critical or flag gaps in Eric’s ideas, that’s only because I don’t feel the need to reiterate all the points I agree with! At a high level, these are:

We need more new institutions to enable research beyond FROs and ARPAs.

A contract research organization will probably need to fund initial capital expenses differently than how it funds most of its operations.

I don’t have much to add on #2, but I think Eric actually understates the importance of #1. There is much more to be written about why changes to the research ecosystem are bottlenecked by where the work is done, but in a nutshell:

Great past ARPA performance depended on orgs like BBN that no longer exist; thus, new ARPAs are constrained by their choice of performers — universities, big companies, and startups all have incentives that reduce ARPA effectiveness.

Thus, we need new institutions for people to actually do research work. FROs are one such institution, but the focus, scope and time-bound nature mean that there is a lot of work and many types of people that they won’t cover.

Unmentioned organizations

The piece fails to mention that there are many organizations that do contract research and engineering. From big ones like SRI International to small shops like Cofab Design or Apogee Research. Heck, most corporate research labs have, to some extent, become contract research orgs because of external funding mandates. Even BBN still technically exists! I’ve included a non-exclusive list of the organizations I’m aware of at the bottom of this piece so that readers can argue with me about why they should or should not be on the list.

The trick is, we no longer think of most of these organizations as doing paradigm-shifting work like building the ARPAnet or unlocking self-driving cars. Many of these organizations did do ambitious research in the period where BBN was also active. SRI International did groundbreaking work in robotics, and human-computer interaction, HRL Laboratories created the first laser and atomic clocks, etc.

In the pharma world, many contract research organizations exist. However, working there is a low status job (relative to their other options) that ambitious scientists and technologists generally don’t pursue.

These patterns suggests that the world that enabled BBN to be successful has changed, and the challenge is to figure out how and whether it’s possible to do ambitious contract-funded research in the 21st century.

Funding research with contracts

The two core core questions to the BBN model are:

What does it take to fund frontier research through contracts?

Can you achieve these conditions in the 21st century?

The abstract answer to the first question is some combination of two things: “alignment” and “margins.”

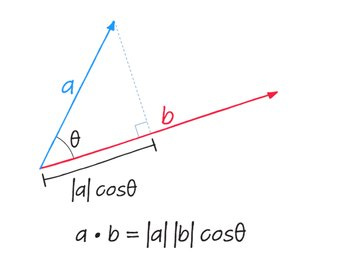

Alignment is the idea that there will always be some difference between the research direction that the researchers/organization want to go and the direction the customer wants to go. The smaller the difference the greater the alignment. (My engineer-brain thinks of alignment as the dot product between two high-dimensional vectors.)

Margins are just how much money the organization makes from a contract on top of all the expenses associated with the contract. These expenses include the obvious like researcher salaries and equipment, but also things like administration, facilities, and soles work to secure the contract in the first place.

An organization funded by contracts can do frontier research if it manages to acquire contracts to do roughly what it wants to do anyway or if it can make enough money doing things that it wouldn’t do anyway that it can afford to do what it actually wants to do “on the side.” (For example, a contract that demanded 50% of a researchers’ time, but had enough margins to cover the other 50% as well.) In the jargon of aerospace and defense contracts, in order to do frontier research work, either an org needs to have strong alignment around external R&D (ERAD) or be able to command large enough margins to do internal R&D (IRAD).

My concern is that both margins and alignment were much easier to come by in the mid 20th century than today.

First let’s look at alignment. One of the reasons we need new research organizations is because of failures in the existing research ecosystem, both of imagination and nerve. Most contract research is for incremental improvements, short time horizons, and existing paradigms. I don’t see a lot of unmet demand for the kinds of frontier-pushing technology research that we associate with ARPAnet or autonomous vehicles in the 90s. What’s my evidence for this?

Personal experience: I’ve tried to sell that kind of work and failed. But of course that could be a skill issue.

Looking at the portfolios of actually existing contract research organizations: there is certainly good work going on, but it doesn’t have the scope or ambition that I would hope for.

The trends of organizations that fund contract research: The government has spent money on researching truly insane things — from nuclear-bomb-powered spacecraft to psychic powers. While some of this still goes on, the level of accountability for government research spending has steadily increased over time, especially outside narrowly-defined defense-related work. The same is true for many large companies, who have no budget for doing exploratory research internally, let alone via external orgs. (This trend is tightly coupled to the rise of corporate venture capital — let VCs and the government fund ambitious R&D and then acquire/invest in the technology as it becomes more mature.)

Now let’s look at Margins. I don’t have hard data on this, but my sense is that the margins on research contracts have decreased since the mid-20th century. That sense is based primarily on the fact that actually existing contract research orgs do little to no internal R&D: everything they do needs to be associated with a contract. The one contemporary organization that Eric mentions very briefly — Otherlab — does almost no work that is not directly on a contract. (Digging into the “why” is a much longer discussion.)

Furthermore, the sales cycles for research contracts have become a much more involved thing, which further eats into margins. This quote from a BBN founder illustrates that shift. (Emphasis added.)

Lick and I took off for Washington D.C. to seek research contracts that would make use of this machine, which carried a price tag of $150,000 (~$1.5 million today). Our visits to the Department of Education, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, NASA, and the Department of Defense proved Lick’s convictions correct, and we soon secured several important contracts.

First, it’s now incredibly hard to waltz into government agencies and pitch a contract that doesn’t have existing appropriation and an open call. (See point above about accountability.) Even in situations where you can pitch to the government the sales cycle is on the order of years, not a single trip. Large companies aren’t much better.

In addition to decreasing margins, longer sales cycles make it harder to run a contract research org because it makes planning and hiring harder. If it takes a year to close a deal, you can only really propose contracts that you have the staff to execute on: researchers aren’t particularly fungible, so you can’t be sure that you’ll be able to hire who you need. If the sales cycles were shorter, you could propose a contract that would enable you to hire someone who is (temporarily) on the market.

Staffing is also a more general concern for the model: say you hire a number of experts for a contract; what do you do when it ends? A contract research organization can quickly become an organization devoted to trying to get contracts just to keep people employed, regardless of how useful the work is. This trap is one of the things the FRO model is designed to avoid. However, there is a lot of value to building institutional knowledge, culture, and infrastructure. It’s not clear how to resolve this tension, but I suspect that the boiling cauldrons and strike teams model has something to do that (consider this a stub for a future post), but I’m not sure how to operationalize funding that model outside of grants/philanthropy yet.

Possibilities

Despite all these reservations, I think Eric is on to something. However, I think that creating an ambitious research organization that doesn’t just depend on philanthropy and grants requires some new ideas beyond “do what BBN did.”

One high-level idea is “go where the margins are” — in the past it was in government spending and computers. Now they’re in AI and drugs (and anywhere else?) The trick that I want to figure out is how to turn those margins into things beyond therapeutics, chips, and things that live behind screens.

Some more concrete ideas. In reality, the business model is probably going to be some combination of these and grants and philanthropy.

Maybe there is a way to work with startups that are building research adjacent products, either directly or as a consortium. Many manufacturing startups could benefit from open-source, parametric, differentiable CAD+CAM. Many fusion startups could benefit from ductile, low-activation materials.

Renting lab space and specialized equipment to other organizations.

Incubating and hosting FROs

(In the long run) selling IP and spinning out companies.